|

Introduction

The etiology for the majority of small bowel obstruction cases results from postoperative adhesions and hernia.1 Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal system. It originates from failure of the vitelline duct to obliterate completely, which is usually located on the antimesenteric border of the ileum. Its incidence is between 1% and 3%. Meckel’s diverticulum occurs with equal frequency in both sexes, but symptoms from complications are more common in male patients. Most of the Meckel’s diverticula are discovered incidentally during a surgical procedure performed for other reasons. Hemorrhage, small bowel obstruction, and diverticulitis are the most frequent complications.2 Histologically, heterotopic gastric and pancreatic mucosas are frequently observed in the diverticula of symptomatic patients. Involvement of the mesodiverticular band of the diverticulum is rarely seen. This case report presents the diagnosis and management of a small bowel obstruction due to mesodiverticular band of a Meckel’s diverticulum.

Case Report

A 26 year-old male with no previous abdominal surgery, presented to the Accident and Emergency Department, Buraimi Hospital, Oman, with severe abdominal pain and vomiting of three days duration. His abdomen was very tender and distended, and bowel sounds were hyperactive. No masses were palpable. There was no significant medical history and his body temperature was normal. Laboratory findings showed a leukocyte count of 15 x 109/L, whereas the hemoglobin and platelet values were 13 g/dl and 276,000, respectively. All other studies, including electrolytes and urinalysis were within normal limits. His erect abdominal plain X-ray showed dilated loops of small bowel, with no free air under either diaphragm. He was diagnosed with mechanical intestinal obstruction, and admitted to the surgical ward with initial management of intravenous fluid resuscitation, nasogastric tube insertion and catheterization. Over the next 12 hours, the patient's vital signs remained stable and his condition did not deteriorate further.

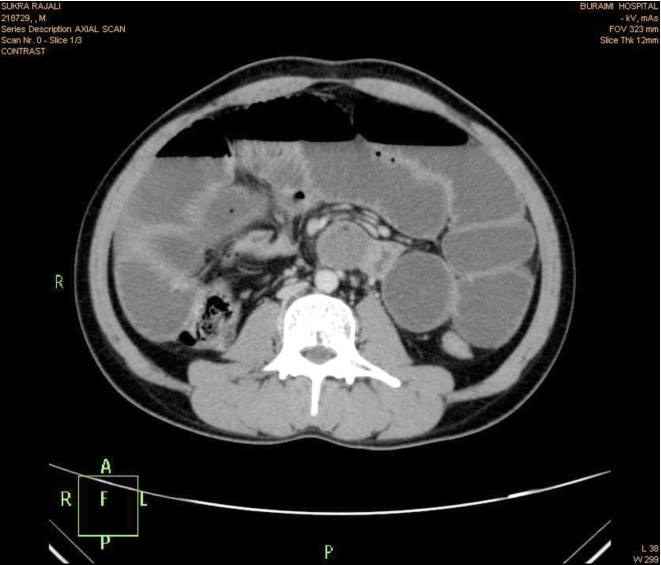

To identify the cause of the small bowel obstruction, computerized tomographic imaging of the abdomen with oral contrast was performed which revealed dilated loops of small bowel with a stricture in the ileum and collapse of the distal ileum and large bowel, (Figs. 1,2,3,4). As the etiology of the stricture remained unidentified, the decision was made to perform a diagnostic laparotomy and manage the patient accordingly. Emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed under general anesthesia, (Figs. 5,6).

Figure 1: Computerized Tomographic imaging of the abdomen with oral contrast.

Figure 2: Dilated loops of small bowel.

Figure 3: Computerized Tomographic imaging of the abdomen.

Figure 4: Computerized Tomographic imaging of the abdomen.

Figure 5: Exploratory laparotomy.

Figure 6: Exploratory laparotomy.

On entering the peritoneal cavity; gross distension of the small bowel and collapse of the large bowel was identified. The small bowel was subsequently delivered carefully and examined. Loops of distended small bowel were identified extending proximally from the duodenojejunal junction to the distal ileum. The distal part of the ileum was found to be markedly compressed by the mesodiverticular band within an area 60 cm proximal to the end of the ileum. Ileal loops were dilated at the superior part of the mechanical obstruction. Obstruction was caused by trapping of a bowel loop by a mesodiverticular band. After separating the mesodiverticular band from the mesenterium, the ileal loop was released from the diverticulum. Resection of the Meckel’s diverticulum with closure of the bowel was performed. The small bowel was then decompressed and the content was gently milked into the stomach before being aspirated via the nasogastric tube. The loops of the bowel were then returned into the abdomen in sequence. Closure of the abdomen was performed using loop sutures. The diverticulum was confirmed as Meckel’s diverticulum by histological examination. The patient recovered without any complications and was discharged after five days of hospitalization.

Discussion

Meckel’s diverticulum was originally described by Fabricius Hildanus in 1598. However, it is named after Johann Friedrich Meckel, who established its embryonic origin in 1809. Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital anomaly of the small intestine, with a prevalence of approximately 1-3%, and is a true diverticulum containing all layers of the bowel wall. The average length of a Meckel’s diverticulum is 3 cm, with 90% ranging between 1 cm and 10 cm, and the longest being 100 cm. This diverticulum is usually found within 100 cm of the ileocaecal valve on the antimesenteric border of the ileum. The mean distance from the ileocaecal valve seems to vary with age, and the average distance for children under 2 years of age is known to be 34 cm. For adults, the average distance of the Meckel’s diverticulum from the ileocaecal valve is 67 cm. Most cases of Meckel’s diverticulum are asymptomatic, and the estimated risk of developing lifetime complications of Meckel’s diverticulum is around 4%.3 Most patients are asymptomatic and the diagnosis is difficult to confirm preoperatively. Among the symptomatic patients, two types of heterotopic mucosa (gastric and pancreatic) are found histologically within the diverticula. The frequent complications of Meckel’s diverticulum are hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction and diverticulitis. Intestinal obstruction is the second most common complication of Meckel’s diverticulum.4

There are plenty of mechanisms for bowel obstruction arising from a Meckel’s diverticulum. Obstruction can be caused by trapping of a bowel loop by a mesodiverticular band, a volvulus of the diverticulum around a mesodiverticular band, and intussusception, as well as by an extension into a hernia sac (Littre’s hernia).5 Similarly, as in our case; obstruction can be caused by trapping of a bowel loop by a mesodiverticular band. The important aspect of our case is clear demonstration of the mesodiverticular band of a Meckel’s diverticulum. Various imaging modalities have been used for diagnosing Meckel’s diverticulum. Conventional radiographic examination is of limited value. Although of limited value, sonography has been used for the investigation of Meckel’s diverticulum. High-resolution sonography usually shows a fluid-filled structure in the right lower quadrant having the appearance of a blind-ending, thick-walled loop of bowel.6 On computed tomography (CT), Meckel’s diverticulum is difficult to distinguish from normal small bowel in uncomplicated cases. However, a blind-ending fluid or gas-filled structure in continuity with the small bowel may be revealed.7 Abdominal CT is used for complicated cases such as intussusceptions. CT can help to confirm the presence of intussusception and distinguish between lead point and non-lead point intussusceptions.8

In asymptomatic patients; whether all cases of incidental Meckel’s diverticula should be resected or not is an unresolved question. On the other hand, for the symptomatic patients; treatment should always include resection of the diverticulum or the segment of the bowel affected by the pathology.3,9

Conclusion

In summary, although Meckel’s diverticulum is the most prevalent congenital abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract; it is often difficult to diagnose. The complications of Meckel’s diverticulum should be taken into account in the differential diagnosis of small bowel obstruction.

Acknowledgements

Authors reported no conflict of interest and no funding was received for this work.

References

1. Foster NM, McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Small bowel obstruction: a population-based appraisal. J Am Coll Surg 2006 Aug;203(2):170-176.

2. Gamblin TC, Glenn J, Herring D, McKinney WB. Bowel obstruction caused by a Meckel’s diverticulum enterolith: a case report and review of the literature. Curr Surg 2003 Jan-Feb;60(1):63-64.

3. Whang EE, Ashley SW, Zimmer MJ. Small intestine. In: F.Charles Brunicardi, editor. Schwart’s Principles of Surgery. McGraw-Hill 2005; pp.1017-1054

4. Nath DS, Morris TA. Small bowel obstruction in an adolescent: a case of Meckel’s diverticulum. Minn Med 2004 Nov;87(11):46-48.

5. Prall RT, Bannon MP, Bharucha AE. Meckel’s diverticulum causing intestinal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 Dec;96(12):3426-3427.

6. Park JJ, Wolff BG, Tollefson MK, Walsh EE, Larson DR. Meckel diverticulum: the Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950-2002). Ann Surg 2005 Mar;241(3):529-533. .

7. Prall RT, Bannon MP, Bharucha AE. Meckel’s diverticulum causing intestinal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 Dec;96(12):3426-3427. .

8. Johnson GF, Verhagen AD. Mesodiverticular band. Radiology 1977 May;123(2):409-412.

9. Evers BM. Small bowel. in: Courtney M. Townsend jr., editor. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. W.B. Saunders 2001; pp.: 873-916.

|