|

Abstract

Objective: This research attempted to explore the public healthcare providers understanding the quality dimensions and patient priorities in Oman. It also addresses the issue of risks confronting health professionals in management without “a customer focused” approach.

Methods: A descriptive study was carried out using a self-administered questionnaire distributed around two tertiary public hospitals. A total of 838 respondents from several specialties and levels of hierarchy participated in the study. The data was analyzed to compare the perception of two groups; the group of junior and frontline staff, as well as of managers and senior staff involved in management.

Results: The results showed that 61% of the junior and frontline staff, and 68.3% of the senior staff and managers think that cure or improvement in overall health is the single most importantquality dimension in healthcare. Both groups perceive that technical dimensions have greater importance (to patients) over interpersonal aspects such as communication with the exception of dignity and respect. There was no significant difference between the perception of the managers and senior staff vis-à-vis the perception of junior and frontline staff on the importance of technical dimensions and the interpersonal aspects of service quality. Despite the proven contribution of empathy to patient satisfaction, it was ranked by both groups as the least important among the dimensions examined.

Conclusion: The findings of this research are therefore informative of the need to implement strategies that deal effectively with such attitudes and create the platform and programs that reinforcethe culture of good quality service amongst healthcare providers, managers in particular, and to improve patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Healthcare quality; Staff perceptions; Patient priorities; Quality dimensions; Functional quality.

Introduction

The consumerization of healthcare has put more emphasis on patient-doctor relationship and on giving patients a more active role in the decision making in the diagnosis and treatment process.1 Patients desire a shift from the usual classic approach in which the doctor has a dominant role and makes the decision on their own, to a more informative, shared and negotiated approach in which the patient can exchange information with healthcare staff and have a more active role in decision making.2,3

Healthcare quality research consistently indicates that the personalized care is of crucial importance to patients and is associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction.4-6 The difference between healthcare service and other services and the trust relationship that must be established between health professionals and patients requires a deeper understanding of the priorities of patients in the medical set-up.7

It is important to look at how the management’s understanding of patient priorities differs from the understanding of those who are in direct contact with patients considering the responsibility of managers for the degree to which culture is created and climate is implemented and sustained, not only setting up quality improvement programs. A shared perspective between managers and their clinical staff (not only frontline staff) on quality improvement program's allows for the most effective implementation and increases the program's success, but managers are expected to have a stronger customer focus, and a broader organizational perspective.

Several studies suggest that there may be discrepancies between managerial and frontline views on certain aspects associated with quality improvement.8,9 Although physicians and other medical staff typically have close interactions with their patients, they stand accused in the literature of not adequately understanding the priorities of their patients.

Looking at the literature, many differences are attributed to the perceptions of healthcare service quality among the different stakeholders in healthcare organizations, not only between health service providers and recipients. Health professionals, physicians in particular, tend to give high importance to clinical outcome and technical quality dimensions, whereas managerial quality perception can be seen as the connecting link between the understanding of patients and professionals. Managers are inclined to be driven by financial considerations to emphasize patient satisfaction and other functional facets of quality as well as financial and clinical outcomes. However, the contradictory findings of Silvestro (2005) and June et al. (1998) regarding the views of managers in comparison to their frontline staff demonstrate a gap in the literature and motivate further research to explore managers' opinions on patient priorities.10,11

Another gap in the literature is the exploration of the perception of health professionals involved in management with clinical background. Regardless of the fact that managers of services are expected to have a stronger customer focus, and a broader organizational perspective; senior health professionals in local public health service may have managerial duties such as being team leaders and committee chairpersons, despite their misconceptions about patients’ concerns. In view of the divergence of theoretical possibilities and the empirical findings, it would be interesting to explore the understanding of the provider at different levels on patient priorities.

This research aims to estimate the relative importance of healthcare quality dimensions to patients in the view of staff at different levels of the public health service in Oman. The hypotheses are as follows:

Clinical outcome is the most important healthcare service quality dimension in the view of frontline and junior staff but not in the view of senior staff and managers in public healthcare service.

There is a difference in the relative importance of health service quality dimensions in the view of frontline junior staff against the view of senior staff and managers.

There is a difference in the perception of the importance of communication and empathy to patients, between the frontline junior staff vs. the senior staff and managers.

Methods

A self-administered questionnaire was drawn based on the dimensions of quality service from SERVQUAL measuring scale.12-14 The overwhelming number of studies on service quality in healthcare has proved SERVQUAL to be a valid measure of service quality.15-18 However, Silvestro’s model was designed to measure staff’s perceptions of patient priorities specifically.11 Thus, the use of attributes based on the dimensions by Parasuraman et al. and by Silvestro (2005) were appropriate tools in this research.11-13

The set of dimensions of Silvestro et al. (2005) and the model specified by Parasuraman et al. in a first stage was modified after a pilot study. The piloting stage highlighted that other attributes such confidentiality of medical information and access were not among patient concerns and were eliminated; whereas, patient safety and revealing a diagnosis are two important attributes which were added. Revealing a diagnosis ensures prompt appropriate intervention and relief from uncertainty and thus was observed by staff in the pilot survey as one of the foremost patient priorities. The pilot also highlighted safety to be a fundamental priority, particularly for patients undergoing procedural or surgical interventions. Comprehensive review of the literature, taking into consideration the social and cultural orientation in which this research is conducted, and the findings of pilot survey, the quality attributes covered were tangibles, responsiveness, communication, revealing correct diagnosis, respect, caring, sympathy, competence, safety, and clinical outcome. Based on the findings of the pilot study, the questionnaire was restructured and some confusing or repetitive items were re-written or removed.

The final version of questionnaire includes in its first section a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from "strongly agree" (5) to "strongly disagree" (1) on the relative importance of items related to quality dimensions. In the second section, the participant was asked to rank 10 items covering different aspects of quality in terms of their importance to patients and their relatives.

The questionnaire obtained information such as name (optional), age, length of experience of the respondent, and designation which allow for us to determine whether the respondent was a junior staff from the frontline group or seniors or rather from the managers group. An effort was made to minimize the number of questions (not at the expense of covering the research questions), to maximize the response rate. The participants are reminded (by bold statements) that they are asked about what they think are the priorities for patients and their relatives rather than what are important quality issues in their view as professionals.

This research was approved by the Research and Ethical Review committee at the Ministry of Health. Answers to the questionnaire were obtained from staff at different levels from several departments at two tertiary public hospitals in Oman, The Royal Hospital and Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, with a wide range of specialties represented in a convenient sample due to limited resources. The aim of the research was to identify the variation of relative importance of quality attributes among two levels of healthcare staff rather than to measure the frequency or distribution of their importance rate. The sample represents a wide range of specialties as it was thought that the clinical specialty of professionals, their profession and the relative position in the hospital hierarchy (frontline patient care vs. managerial responsibility) are the main sources of potential variation. The targeted sample size for the junior and frontline staff group was 800 respondents and 400 respondents for senior staff and managers group. The two hospitals were chosen for the sake of ease of logistics from the standpoint of the principal researcher.

For this study, it was necessary to obtain the designation of the participants in the basic demographic items to determine the group they belong to as managers or as frontline employees. Interns, medical officers, specialists, nurses, receptionists, clerks and junior staff from supportive services all belong to the frontline employees. From the supportive services, participants in the study were only those in contact with patients as part of their routine activities such as medical records and dietetic services.

Senior consultants, senior specialists, senior ward nurses, senior unit nurses, senior administrative staff and managers of clinical units and supportive services were all included in the senior staff group since they usually hold managerial roles and/or are directly or indirectly involved in decision making even at the strategic level (personal observation). Moreover, senior health professionals are usually permanent, (as they are not rotating and or involved in training programs) and thus are more likely to get involved in any quality improvement programs. The software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 was used to analyze the data.

Results

The group that participated most significantly in this research were nurses. Junior nurses who are frontline staff constituted 50.8% of the sample, whereas ward nurses and senior staff nurses who are usually involved in management comprised 22.4% of the respondents. This is not surprising as in tertiary healthcare, there is usually a dominance of nurses in the workforce. In contrast, doctors had a contribution of 13% (8.7% were junior doctors [medical officers and junior specialists] and 4.3% were senior doctors who usually have managerial and supervisory responsibility as well as their clinical duties). Managers from administration, (without any involvement in clinical tasks) formed only 2.3% of the studied sample. While employees from medical records department and other supportive services comprised 11.5% of the respondents.

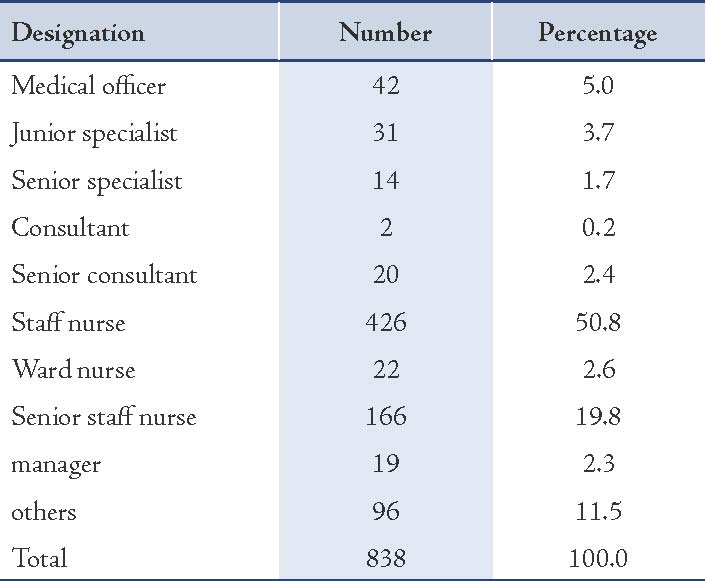

The response rate for the total sample was 69.8%. The response rate for the junior and frontline staff group was greater than the group of senior staff and managers, 74.4% and 60.8%, respectively. The sample heterogeneity according to designation is represented in Table 1.

Table 1: The sample heterogeneity according to designation.

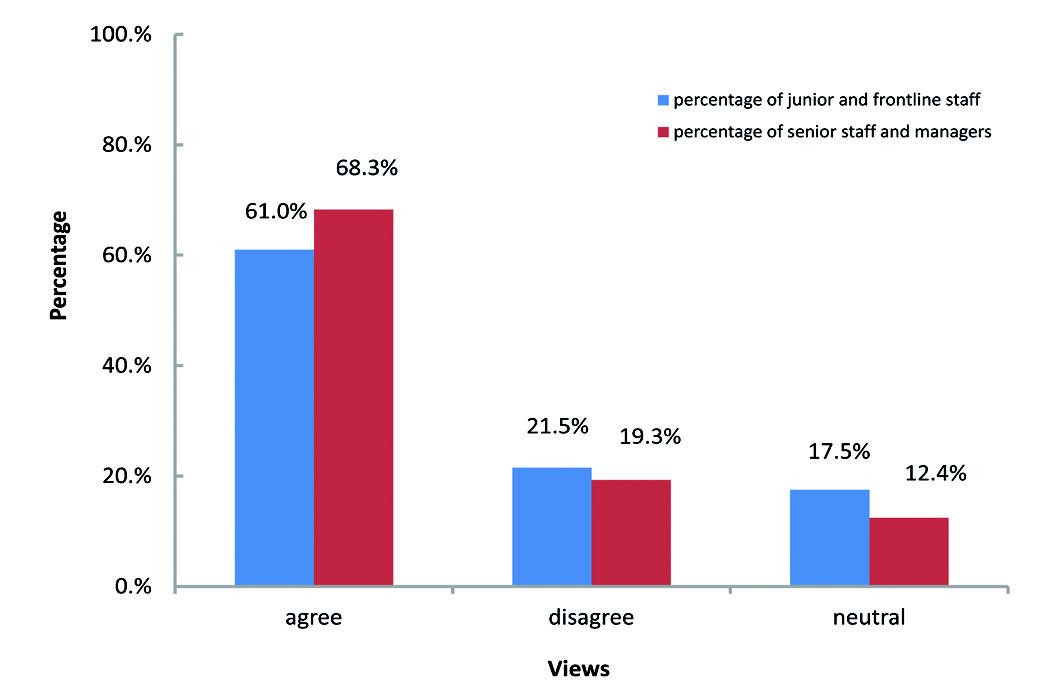

For the first hypothesis (H1); Clinical outcome was the most important healthcare service quality dimension in the view of frontline and junior staff but not in the view of senior staff or managers in public healthcare service. The results (Fig. 1) show that 61% of the junior and frontline staff, and 68.3% of the senior staff and managers thought that cure or improvement in overall health is the single most important quality dimension in healthcare. There is no statistically significant difference between the two groups in their view to the importance of this quality dimension (p=0.181).

Figure 1: View on cure or improvement in overall health is the most important quality dimension for patients and their families.

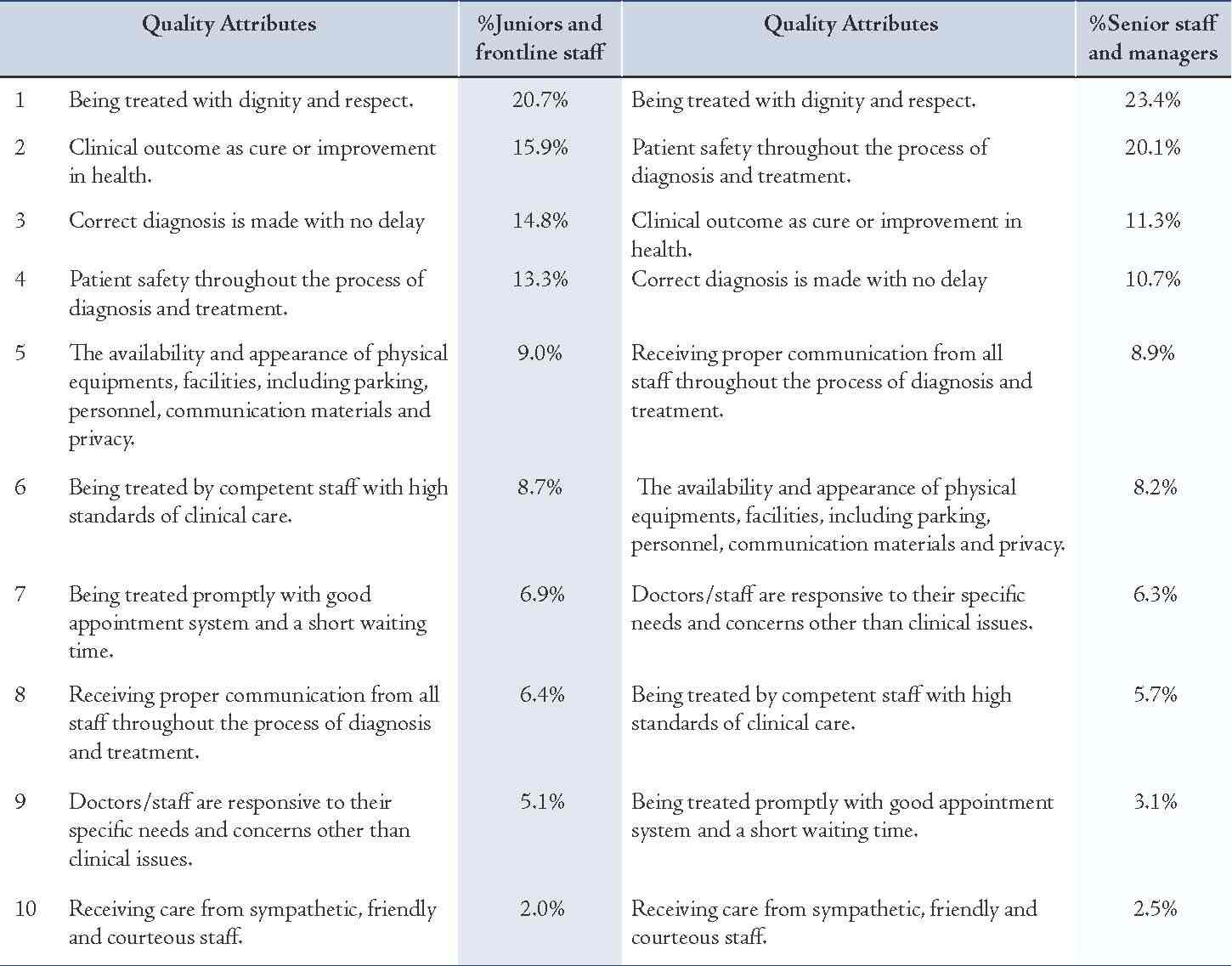

On the second hypothesis (H2); there was a difference in the relative importance of health service quality dimensions in the view of frontline junior staff against the view of senior staff and managers. Table 2 presents a comparison of ranking of quality attributes between the two groups. The percentages of respondents who ranked the attribute as the most important within their group are given. The perception of some staff at different levels is that clinical outcome is not the most important attribute to quality. It is the second in the perception of some of the junior and frontline staff and it comes third in the ranking in the view of senior staff and managers.

While "being treated with dignity and respect" is perceived by both groups of respondents as the most important quality dimension to patients. Interestingly, both groups share the same view on ranking the first four attributes, namely "being treated with dignity and respect," "clinical outcome as cure or improvement in health," "correct diagnosis is made with no delay," and "patient safety throughout the process of diagnosis and treatment." Unexpectedly, both groups ranked "receiving care from sympathetic, friendly and courteous staff" as the least important quality dimension. Again, the Chi-square tests showed no significant difference between the two groups.

On the third hypothesis (H3); there was a difference in the perception of the importance of communication and empathy to patients between the frontline junior staff vs. the senior staff and managers.

A. Views of the two groups on staff communication, professionalism and empathy are more important for patients and their families than cure or improvement in overall health.

The results show that 40.5% and 45.7% of junior and frontline staff group and senior staff and managers group, respectively, agree on the view that staff communication, professionalism and empathy are more important for patients and families than cure or improvement in overall health. There was no statistically significant difference between the views of the two groups (p=0.218).

B. Views of the two groups on "receiving care from friendly and sympathetic doctors and nurses is less important for patients and families than their skills and competence."

Most of the staff at different levels disagreed that receiving care from friendly and sympathetic doctors and nurses is less important for patients and families than their skills and competence. Hence, there was no statistically significant difference between the views of both groups (p=0.183).

C. Views of the two groups on "for patients and their families, being courteous, empathic, friendly and considerate are more important features of staff in general than competency and knowledge."

Only less than half of staff at different levels agreed that being courteous, empathic, friendly and considerate were important features of staff in general than competency and knowledge. About a third of both groups disagreed, whereas a quarter from both groups were not sure. There was no statistically significant difference between the views of the two groups in this aspect (p=0.659).

Table 2. Comparison of the ranking of quality attributes according to views of the two groups.

Discussion

In contrast to most empirical research in literature and the expectations that managers may have more "customer satisfaction" focused approach, the findings of this research confirm that the perception of the senior staff and managers of the relative importance of clinical outcome amongst quality dimensions does not significantly differ from the view of the junior and frontline staff.

The results also confirm that perception of some staff at different levels is that clinical outcome is not the most important dimension of quality. It was ranked second in the perception of some junior and frontline staff and it came third in the view of most senior staff and managers. However, this difference was not statistically significant and it does not contradict the result on the first hypothesis of this research. It is possible that some respondents agreed on the statement, "Cure or improvement in overall health is the most important for patients and family than any other health care quality issue," but when they answered the ranking question, they did not rank clinical outcome as the most important dimension. This may reflect their irrational judgement or their unfamiliarity about the dimensions and that they became aware of them only when they were asked to rank the different dimensions. Interestingly, "being treated with dignity and respect" was perceived by both groups of respondents as the most important quality dimension to patients. This is not surprising considering that most of recipients of public health services are not desperate for the public services and can afford to go to private health services as an alternative (personal communication).

Both groups share almost the same view on the first four attributes ranked, namely "being treated with dignity and respect," "clinical outcome as cure or improvement in health," "correct diagnosis is made with no delay," and "patient safety throughout the process of diagnosis and treatment." This might be attributed to the organizational culture and it reflects the fact that most of those who are involved in managerial decisions are themselves health professionals, sharing attitudes and beliefs with their junior staff. Moreover, in tertiary hospitals, where junior professionals are practicing as part of their training programs, they learn from their senior colleagues. This socialization process not only shapes their personality but also the practice and attitudes towards pateints, and interaction with the recipients of the service.

It is not surprising that revealing diagnosis is one of patients’ priorities and it was ranked third priority by junior and frontlines staff perception, and fourth by senior staff and managers’ perception. It relieves uncertainty, enhances trust on staff and encourages commitment to treatment and surveillance plan. Patient safety, the dimension that was not even included in some relevant research, was perceived fourth by junior and frontline employees and second by senior staff and managers. It was examined in this research following comments on the pilot study that a lot of patients have mistrust and doubt on the quality of public health services.

Unexpectedly, both groups ranked "receiving care from sympathetic, friendly and courteous staff" as the least important quality dimension compared to the other quality dimensions examined. The literature shows that empathy is not given importance by health professionals anyway,19,20 but what is surprising is that despite the proven remarkable contribution of these attributes to patient satisfaction, they are viewed as the least important by managers. In the author’s view, the organizational culture which undermines interpersonal attributes of quality and focuses on technical aspects to improve clinical outcome and performance in measurable clinical indicators (personal observation) is the possible explanation for this finding. The workload and time pressure in busy tertiary hospitals make this explanation more likely as health professionals themselves are under stress and are usually too busy to spend enough time with families to dig into the psychosocial aspects of the illness, sympathize and show concern and support. Moreover, there might be a lack of knowledge about the importance of some quality dimensions (other than the visible technical ones), the affective attributes in particular and their role in patient satisfaction. As patient expectations for service quality are possibly viewed as less important than clinical outcome, they are more likely to be misunderstood or taken lightly.

One important finding from this research is that health professionals with managerial positions have different perception from the perception of qualified managers whose view on quality is more oriented to some "whole organization-related" aspects. This suggests a lack of awareness about the trend of consumerization of health services and the shift from the usual classic approach to a more informative, shared and negotiated approach in which the patient have a more active role in the decision making. Not surprising was the lack of knowledge of these issues among staff at different levels, which is likely to create a culture where interpersonal attributes are given minimal attention. It becomes a vicious cycle when providers do not listen to their patients and then do not understand what may satisfy them and as a result, they tend to further ignore some patients’ concerns and misunderstand their priorities. This might be further enhanced by tendencies towards academic and scientific pursuits rather than humanistic and patient centered care.

According to O’Connor et al. (2000), medical and nursing students seem to arrive at medical or nursing college with a misunderstanding of patient expectations for some quality dimensions of health service and these misconceptions do not change as they progress through the years of their study or post graduate training and thus continue when the health professionals progress to more senior roles where they are involved in managerial tasks.21 Unlike qualified managers (who have stronger customer focus, broader organizational perspective, specific management education and training), perhaps they become involved in management with minimal understanding of the managerial issues. Protective practice of medicine and litigation, driven by education and higher public expectations might be a possible explanation for the importance given to technical outcome and revealing diagnosis to start appropriate treatment on time. Moreover, empathy and other affective attributes are not in the specification of the service over which professionals can be questioned. In contrast, "being treated with dignity and respect" which was perceived as the most important quality attribute, if breached, is a valid reason for litigation in the national law.

The dimensions of revealing diagnosis, clinical outcome, and patient safety which are all within the first four quality dimensions ranked in terms of importance perceived by both groups are all technical in nature and are assessed from the professionals’ point of view to some extent. This is in keeping with the empirical findings of June et al. (1998) that physicians view themselves more like scientists who look at the outcome, not the emotional, personal or human side of their service performance.10 However, according to Lee et al. (2000), considering the potentially fatal and irrevocable consequences of malpractice in healthcare in contrast to other services, it might be logical and desirable for physicians to focus on the result of the performance, especially if they do not put emphasis on patient-provider relationship to have a chance to understand other patient priorities.22 The view of putting patient satisfaction as a top priority might be debatable when the limited resources entrusted to public services by the government force providers to focus on technical aspects of care. This may be the view of some managers who put financial issues in their consideration when managing the services, not only health professionals who used to practice with a cost effective approach.

Conclusion

Leaders of health services should focus on methods to change not only their systems but cultures of their organizations to enhance the patient focused approach and give more attention to interpersonal issues of the functional quality. They should work to make their hospitals learning organizations by continuous monitoring and research activities for functional aspects of care similar to the attention given to the research of clinical aspects, not only because the focus on the various dimensions of quality can help to set administrative priorities but also to help the professionals to closely evaluate the gap caused by their misconceptions. The only sustainable competitive advantage today is the ability to change, adapt, and evolve and to do it better than the competition.

Further research looking at the understanding of different segments of healthcare systems and at different situations concerning management issues and causes of misconceptions are needed to develop appropriate approaches to deal with them. This research, in contrast to most published relevant researches, examines providers’ understanding of healthcare quality dimensions rather than recipients' perceived quality dimensions, and focuses on staff understanding of patient priorities at different levels in public healthcare in Oman, highlighting the gap in understanding of health professionals taking managerial tasks about the consumerization of healthcare and the customer/patient oriented approach.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of our colleagues Hilal Al Kharousi and Sultan Al Marhoobi in preparing and distributing the questionnaire and data analysis. We are also grateful to the staff of The Royal Hospital and Sultan Qaboos University Hospital for taking interest and participating in the research, as well as providing valuable help in distributing the questionnaires.

References

1. Laing A, Hogg G. Political exhortation, patient expectation and professional execution: perspectives on the consumerization of health care. Br J Manage 2002;13(2):173-188 .

2. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med 1999 Sep;49(5):651-661.

3. Hausman A. Modeling the patient-physician encounter: improving patient outcomes. Academy of Marketing Science Journal 2004;32(4):403-417 .

4. Fung CH, Elliott MN, Hays RD, Kahn KL, Kanouse DE, McGlynn EA, et al. Patients’ preferences for technical versus interpersonal quality when selecting a primary care physician. Health Serv Res 2005 Aug;40(4):957-977.

5. Drain M, Kaldenberg D. Building patient loyalty and trust: the role of patient satisfaction. Group Pract J 1999;48(9):32-35.

6. Drain M. Quality improvement in primary care and the importance of patient perceptions. J Ambul Care Manage 2001 Apr;24(2):30-46.

7. Berry LL, Bendapudi N. Health care: a fertile field for service research. J Serv Res 2007;10(2):111-122 .

8. Price ML, Fitzgerald L, Kinsman L. Quality improvement: the divergent views of managers and clinicians. J Nurs Manag 2007 Jan;15(1):43-50.

9. Singer SJ, Falwell A, Gaba DM, Baker LC. Patient safety climate in US hospitals: variation by management level. Med Care 2008 Nov;46(11):1149-1156.

10. Jun M, Peterson RT, Zsidisin GA. The identification and measurement of quality dimensions in health care: focus group interview results. Health Care Manage Rev 1998;23(4):81-96.

11. Silvestro R. Applying gap analysis in the health service to inform the service improvement agenda. Int J Qual Reliab Manage 2005;22(3):215-233 .

12. Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. SERVQUAL: a multiple item scale for measuring customer perceptions of service quality. J Retailing 1988;64(1):12-37.

13. Parasuraman A, Berry LL, Zeithmal V. Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J Retailing 1991;67(4):420-450.

14. Zeithaml VA, Parasuraman A, Berry LL. Delivering Quality Service: Balancing Customer Perceptions and Expectations, New York, The Free Press, 1990.

15. Babakus E, Mangold WG. Adapting the SERVQUAL scale to hospital services: an empirical investigation. Health Serv Res 1992 Feb;26(6):767-786.

16. Taylor SA, Cronin JJ Jr. Modeling patient satisfaction and service quality. J Health Care Mark 1994;14(1):34-44.

17. Dean AM. The applicability of SERVQUAL in different health care environments. Health Mark Q 1999;16(3):1-21.

18. Wong J. Service quality measurement in a medical imaging department. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2002;15(2):206-212 .

19. Kent G, Wills G, Faulkner A, Parry G, Whipp M, Coleman R. Patient reactions to met and unmet psychological need: a critical incident analysis. Patient Educ Couns 1996 Jul;28(2):187-190.

20. Reynolds WJ, Scott B. Do nurses and other professional helpers normally display much empathy? J Adv Nurs 2000 Jan;31(1):226-234.

21. O’Connor SJ, Trinh HQ, Shewchuk RM. Perceptual gaps in understanding patient expectations for health care service quality. Health Care Manage Rev 2000;25(2):7-23.

22. Lee H, Delene ML, Bunda MA, Kim Ch. Methods of measuring Health-Care service quality. J Bus Res 200.

|