Hypertension is a common leading cause of morbidity and mortality, and is an important risk factor for cardiovascular and chronic kidney diseases.1,2 Hypertension in pregnancy has been associated with a higher risk for developing cardiovascular diseases later in life.3,4 This might be due to the irreversible vascular and metabolic changes that may persist after the complicated pregnancy. Therefore, managing hypertension in pregnancy does not only improve the immediately affected pregnancy but also the long-term maternal cardiovascular health.4

In pregnancy, hypertension is considered the second most common cause of direct maternal death and causes complications in approximately 7% of pregnancies;5,6 3% of whom have pre-existing hypertension before pregnancy, and 4% develop hypertension during pregnancy, the latter increasing the risk of developing preeclampsia.5

Although the use of medications during pregnancy is generally avoided, normalizing blood pressure in pregnancy is crucial due to the major adverse perinatal outcomes that hypertension can cause.5 Studies have shown that methyldopa and labetalol used to control blood pressure in pregnancy significantly reduces the incidence of preterm deliveries (PTD), small for gestational age (SGA), and admissions to the neonatal unit.7 However, studies have shown that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are teratogenic and linked to major fetal malformations. Therefore, their use in pregnancy is contraindicated.5 In the management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, labetalol is recommended as first-line therapy, but intravenous hydralazine and oral nifedipine can also be used. Moreover, methyldopa is recommended as first-line therapy in managing pre-existing hypertension in pregnancy in addition to labetalol, nifedipine, and a diuretic.8 However, some studies have linked these antihypertensive medications used in pregnancy to potential adverse outcomes in the child, such as decreased birth weight, cognitive development delay, childhood depression,9 higher risk for developing asthma and sleeping disorders during childhood,6 neonatal seizures, and hematological disorders.5 Nonetheless, there is still no strong evidence supporting and confirming these associations, and the potential adverse effects of these antihypertensive drugs on pregnancy and the newborn are debatable.5,6,9

Despite all these guidelines and studies, the prescribing patterns for control of blood pressure during pregnancy is variable in each institution. Our study aimed to determine the prescribing patterns of antihypertensive drugs during pregnancy in one tertiary university hospital and to study the impact of these drugs on maternal and fetal outcomes.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) in Muscat, Oman. All pregnant women who attended SQUH from January 2015 to September 2018 were screened for eligibility by reviewing the electronic medical records. The inclusion criteria included women who had singleton pregnancy taking antihypertensive medications and who delivered in the hospital. Women with multiple pregnancies, molar pregnancy, not on antihypertensive medications, or who delivered elsewhere were excluded from the study.

The electronic medical records of the eligible patients were reviewed, and data regarding antihypertensive drugs during pregnancy, type of hypertension and the perinatal outcomes, fetal and maternal outcomes were collected.

Patients were diagnosed according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines.10 Gestational hypertension was defined as new-onset hypertension (blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg) after 20 weeks gestation. Preeclampsia was new-onset gestational hypertension accompanied by proteinuria. Chronic hypertension (pre-existing hypertension) was hypertension detected before 20 weeks gestation. Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia is chronic hypertension with proteinuria. Eclampsia was preeclampsia combined with seizures.10

Descriptive statistics were used to obtain frequencies, means, medians, standard deviations (SD), and minimum and maximum of the different variables. The values of the continuous variables were described as mean±SD. The associations of the categorized variables were assessed using the chi-square test. One-way analysis of variance and post hoc analysis were used to compare means of continuous variables and assess their associations with categorized variables. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant for all used statistical tests. We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) for the analysis.

Ethical approval was granted from the Medical Research Ethics Committee, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman (MREC#1697) on 11 July 2018.

Results

The case notes of 484 women were reviewed to assess eligibility for the study according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two hundred and seventy-four women were excluded from the study due to one or more of the exclusion criteria.

The final analysis included 210 women. The mean age of the women was 32.4±5.6 years, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 34.0±8.1 kg/m2. The gravidity ranged from 1 to 15 with a median of 3, and the parity ranged from 0 to 8 with a median of 2. The gestational age at birth ranged from 23 to 42, with a median of 37 weeks [Table 1]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was the most commonly associated comorbidity in the studied population, 82 (39.0%) women were diagnosed with DM, 58 (70.7) women with gestational diabetes, and 24 (29.3%) women with pre-existing diabetes. This was followed by fibroids (5.7%) and hypothyroidism (4.7%).

The most common type of hypertension was preeclampsia (41.4%) followed by chronic hypertension (22.4%), gestational hypertension (20.5%), and chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia (15.7%). More than half of the women (n = 120, 57.1%) developed preeclampsia. Only 27 (12.9%) women had normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, while 183 (87.1%) women required an intervention. The interventions included medial induction of labor in 91 (49.7%) women while 92 (50.3%) required cesarean section.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the hypertensive pregnant women in the studied population.

|

Age, years |

20–46 |

32.4 ± 5.6 |

|

BMI, kg/m2 |

19.5–68.0 |

34.0 ± 8.1 |

|

SBP, mmHg |

127–235 |

160.4 ± 18.1 |

|

DBP, mmHg |

55–154 |

93.7 ± 14.8 |

|

Gravidity |

1–15 |

4.0 ± 2.6 |

|

Parity |

0–8 |

2.0 ± 2.0 |

|

Gestational age, weeks |

23–42 |

36.0 ± 3.5 |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure.

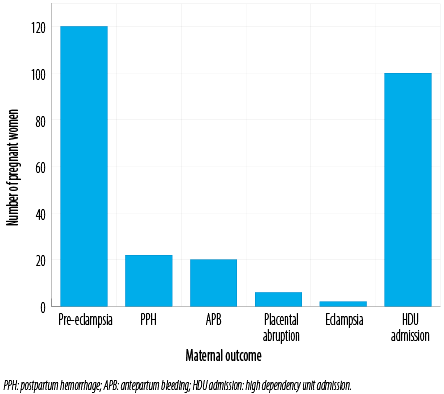

Figure 1: Maternal outcomes of the hypertensive pregnant women in the studied population.

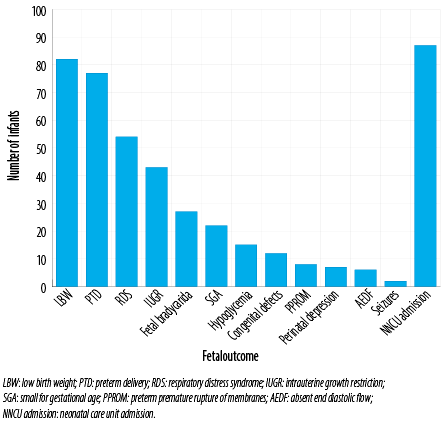

Figure 2: Fetal outcomes of the infants of the hypertensive pregnant women in the studied population.

Table 2: Prevalence of risk factors, fetal and maternal outcomes in the studied population according to the type of hypertensive disorder.

|

Risk factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age, mean ± SD, years |

32.3 ± 5.5 |

30.4 ± 5.6 |

34.1 ± 5.2 |

35.4 ± 4.3 |

32.6 ± 5.5 |

< 0.001 |

|

BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 |

33.5 ± 5.5 |

31.5 ± 9.5 |

36.5 ± 7.5 |

36.4 ± 7.3 |

34.0 ± 8.1 |

0.008 |

|

Associated DM |

13 (30.2) |

26 (29.9) |

28 (59.6) |

15 (45.5) |

82 (39.0) |

0.004 |

|

Fetal outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low birth weight |

9 (21.4) |

46 (55.4) |

10 (21.3) |

17 (51.5) |

82 (40.0) |

< 0.001 |

|

Preterm delivery |

5 (11.9) |

42 (50.6) |

12 (25.5) |

18 (54.5) |

77 (37.6) |

< 0.001 |

|

IUGR |

6 (14.3) |

28 (33.7) |

5 (10.6) |

4 (12.1) |

43 (21.0) |

0.004 |

|

SGA |

4 (9.5) |

17 (20.5) |

4 (8.5) |

2 (6.1) |

27 (13.2) |

0.088 |

|

Hypoglycemia |

4 (9.5) |

6 (7.2) |

1 (2.1) |

4 (12.1) |

15 (7.3) |

0.349 |

|

Congenital defects |

2 (4.8) |

3 (3.6) |

2 (4.3) |

5 (15.2) |

12 (5.9) |

0.100 |

|

Seizures |

1 (2.4) |

1 (1.2) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (1.0) |

0.639 |

|

RDS |

3 (7.1) |

29 (34.9) |

6 (12.8) |

16 (48.5) |

54 (26.3) |

< 0.001 |

|

Fetal bradycardia |

6 (14.3) |

12 (14.5) |

0 (0.0) |

4 (12.1) |

22 (10.7) |

0.058 |

|

Perinatal depression |

1 (2.4) |

2 (2.4) |

2 (4.3) |

2 (6.1) |

7 (3.4) |

0.761 |

|

PPROM |

3 (7.1) |

2 (2.4) |

3 (6.4) |

0 (0.0) |

8 (3.9) |

0.286 |

|

Absent end diastolic flow |

1 (2.4) |

3 (3.6) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (6.1) |

6 (2.9) |

0.433 |

|

NNCU admission |

7 (16.7) |

46 (55.4) |

15 (31.9) |

19 (57.6) |

87 (42.4) |

< 0.001 |

|

Maternal outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eclamptic seizures |

0 (0.0) |

1 (1.1) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (3.0) |

2 (1.0) |

0.491 |

|

Postpartum hemorrhage |

6 (14.0) |

4 (4.6) |

7 (14.9) |

5 (15.2) |

22 (10.5) |

0.138 |

|

Antepartum bleeding |

4 (9.3) |

8 (9.2) |

4 (8.5) |

4 (12.1) |

20 (9.5) |

0.955 |

|

Placental abruption |

0 (0.0) |

4 (4.6) |

1 (2.1) |

1 (3.0) |

6 (2.9) |

0.511 |

G-HTN: gestational hypertension; PE: preeclampsia; C-HTN: chronic hypertension; BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellites; IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction; SGA: small for gestational age; RDS: respiratory distress syndrome; PPROM: preterm premature rupture of membranes; NNCU: neonatal care unit; HDU: high dependency unit.

Table 3: Prevalence of fetal and maternal outcomes in the studied population according to labetalol and methyldopa when prescribed alone.

|

Risk factors |

|

|

|

|

|

Age, mean ± SD, years |

31.9 ± 5.3 |

33.4 ± 4.8 |

32.4 ± 5.2 |

0.150 |

|

Associated DM |

22 (31.0%) |

19 (51.4) |

41 (38.0) |

0.038 |

|

Fetal outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

Low birth weight |

19 (28.8) |

8 (19.5) |

27 (25.2) |

0.283 |

|

Preterm delivery |

7 (10.6) |

8 (19.5) |

15 (13.9) |

0.216 |

|

IUGR |

11 (16.7) |

5 (12.2) |

16 (15.0) |

0.528 |

|

SGA |

5 (7.6) |

2 (4.9) |

7 (6.5) |

0.583 |

|

Hypoglycemia |

5 (7.6) |

1 (2.4) |

6 (5.6) |

0.262 |

|

Congenital defects |

1 (1.5) |

2 (4.9) |

3 (2.8) |

0.306 |

|

Seizures |

0 (0.0) |

1 (2.4) |

1 (0.9) |

0.202 |

|

RDS |

6 (9.1) |

3 (7.3) |

9 (8.4) |

0.748 |

|

Fetal bradycardia |

8 (12.1) |

1 (2.4) |

9 (8.4) |

0.079 |

|

Perinatal depression |

3 (4.5) |

0 (0.0) |

3 (2.8) |

0.166 |

|

PPROM |

2 (3.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (1.9) |

0.261 |

|

Absent end diastolic flow |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

NNCU admission |

21 (31.8) |

5 (12.2) |

26 (24.3) |

0.021 |

|

Maternal outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

Preeclampsia |

33 (50.0) |

7 (16.7) |

40 (37.0) |

< 0.001 |

|

Eclampsia |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

Postpartum hemorrhage |

10 (15.2) |

5 (11.9) |

15 (13.9) |

0.634 |

|

Antepartum bleeding |

7 (10.6) |

5 (11.9) |

12 (11.1) |

0.834 |

|

Placental abruption |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

SD: standard deviation; DM: diabetes mellitus; IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction; SGA: small for gestational age; RDS: respiratory distress syndrome; PPROM: preterm premature rapture of membranes. NNCU: neonatal care unit; HDU: high dependency unit.

Table 4: Prevalence of fetal and maternal outcomes in the studied population in the women who received single medication and the women who received combination therapy.

|

Risk factors |

|

|

|

|

|

Age, mean ± SD, years |

32.4 ± 5.2 |

32.4 ± 6.1 |

32.4 ± 5.6 |

0.952 |

|

Associated DM |

41 (37.6) |

41 (40.6) |

82 (39.0) |

0.658 |

|

Fetal outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

Low birth weight |

27 (25.0) |

55 (56.7) |

82 (40.0) |

< 0.001 |

|

Preterm delivery |

15 (13.9) |

62 (63.9) |

77 (37.6) |

< 0.001 |

|

IUGR |

16 (14.8) |

27 (27.8) |

43 (21.0) |

0.025 |

|

SGA |

7 (6.5) |

20 (20.6) |

27 (13.2) |

0.003 |

|

Hypoglycemia |

6 (5.6) |

9 (9.3) |

15 (7.3) |

0.307 |

|

Congenital defects |

3 (2.8) |

9 (9.3) |

12 (5.9) |

0.048 |

|

Seizures |

1 (0.9) |

1 (1.0) |

2 (1.0) |

0.939 |

|

RDS |

9 (8.3) |

45 (46.4) |

54 (26.3) |

< 0.001 |

|

Fetal bradycardia |

10 (9.3) |

12 (12.4) |

22 (10.7) |

0.472 |

|

Perinatal depression |

3 (2.8) |

4 (4.1) |

7 (3.4) |

0.605 |

|

PPROM |

2 (1.9) |

6 (6.2) |

8 (3.9) |

0.110 |

|

Absent end diastolic flow |

0 (0.0) |

6 (6.2) |

6 (2.9) |

0.009 |

|

NNCU admission |

26 (24.1) |

61 (62.9) |

87 (42.4) |

< 0.001 |

|

Maternal outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

Preeclampsia |

40 (36.7) |

80 (79.2) |

120 (57.1) |

< 0.001 |

|

Eclampsia |

0 (0.0) |

2 (2.0) |

2 (1.0) |

0.140 |

|

Postpartum hemorrhage |

15 (13.8) |

7 (6.9) |

22 (10.5) |

0.106 |

|

Antepartum bleeding |

13 (11.9) |

7 (6.9) |

20 (9.5) |

0.218 |

|

Placental abruption |

0 (0.0) |

6 (5.9) |

6 (2.9) |

0.010 |

SD: standard deviation; DM: diabetes mellitus; IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction; SGA: small for gestational age; RDS: respiratory distress syndrome; PPROM: preterm premature rupture of membranes; NNCU: neonatal care unit; HDU: high dependency unit.

Postpartum hemorrhage was the second most common complication (n = 22, 10.5%). Two women developed eclampsia. Nearly half of the women (47.6%) required admission to the high dependency unit during pregnancy or post-delivery [Figure 1].

There were five cases of intrauterine fetal deaths with 205 live births. The mean Apgar score at one minute was 8.0±1.7 and at five minutes was 9.0±1.1. The mean birth weight was 2.4±0.8 kg.

The fetal outcomes are represented in Figure 2. The most common fetal outcome was low birth weight (LBW) followed by PTD, respiratory distress syndrome, intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), and SGA, respectively. Twelve newborns had a congenital defect including patent ductus arteriosus (n = 6), undescended testes (n = 2), hypospadias

(n = 2), atrial septal defect (n = 1), and cleft lips

(n = 1). Eighty-seven newborns required admission to the neonatal care unit, and there was one fetal mortality immediately after birth.

Table 2 represents the risk factors and fetal and maternal outcomes in the studied population according to the type of hypertensive disorder. Women with preeclampsia were younger and had lower BMI than women with other hypertension types (p < 0.05). DM was more frequent in women with chronic hypertension than other hypertensive disorders (p < 0.05).

LBW, PTD, IUGR, respiratory distress syndrome, and neonatal care unit admissions were significantly higher in women with preeclampsia than in women with other types of hypertension (p < 0.05). The prevalence of SGA and fetal bradycardia were more among women with preeclampsia. However, it was not statistically significant. The other fetal outcomes did not differ significantly between types of hypertension. There was a significant association between the type of hypertension and the admissions to the neonatal care unit for the newborns and to the high dependency unit (HDU) for the mothers (p < 0.001). The other maternal outcomes were not significantly different between the types of hypertension.

Labetalol was the most common prescribed antihypertensive medication in the studied population, 170 (81.0%) women received labetalol followed by methyldopa (n = 74, 35.2%), hydralazine (n = 43, 20.5%), and nifedipine (n = 15, 7.1%). Magnesium sulphate was used in 77 (36.7%) women to prevent eclampsia. There were 101 (48.1%) women on combined therapy. Labetalol was prescribed as a single therapy for 71 (33.8%) women and methyldopa alone for 37 (17.6%) women. One woman had hydralazine alone.

Newborns of the women who received labetalol alone required admission to the neonatal care unit more than those who were on methyldopa alone (31.8% vs. 12.2%, p = 0.021). As expected, fetal bradycardia was higher in fetuses of women who received labetalol. However, it was not statistically different (p = 0.079). The other fetal and maternal outcomes were not significantly different between the two antihypertensive medications [Table 3].

LBW, PTD, IUGR, SGA, respiratory distress syndrome, absent end diastolic flow, congenital defects, and neonatal care unit admissions were significantly more prevalent in the newborns of women who received combination therapy than newborns of women who were on a single medication (p < 0.05). Preeclampsia, placental abruption, and HDU admissions were significantly more prevalent in women on combination therapy than those who received a single medication (p < 0.05). The other maternal outcomes did not differ significantly with the used treatment, single or combination [Table 4].

Discussion

Hypertension in pregnancy has been associated with perinatal, fetal, and maternal adverse outcomes.1 The outcomes found in our study are partially in line with a previously reported retrospective study from Saudi Arabia, which found that preeclampsia was the most common hypertensive disorder in pregnancy (54.9%). However, it was followed by gestational hypertension (29.5%), chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia (4%), and chronic hypertension (3.6%).11 An earlier study from Canada found that the most prevalent hypertensive disorder in pregnancy among their studied population was gestational hypertension (44.4%) followed by chronic hypertension (23.6%), preeclampsia (25.7%), and chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia (6.4%).12

The most common fetal outcomes in our study were LBW, PTD, IUGR, and SGA, consistent with what had been reported recently in a systemic review and another study from Ghana.5,13 Preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage were the most common maternal outcomes in our study, and that is in line with other studies.7

Most of the women in our study were on combination therapy (48.1%), similar to a study from Saudi Arabia (62.5%).11 However, in our study, labetalol (33.8%) was the antihypertensive agent most commonly prescribed on its own followed by methyldopa (17.6%), while in Saudi Arabia methyldopa was most commonly prescribed alone (22.8%) followed by nifedipine (8.5%) and

labetalol (6.3%).

A comparative observational study conducted in India comparing the effects of labetalol and methyldopa on perinatal outcomes showed a non-significantly higher prevalence of IUGR, neonatal care unit admissions, respiratory distress syndrome, and SGA in newborns of women who were on methyldopa than newborns of women who were on labetalol.14 However, as in our study, there was no significant statistical difference in perinatal outcomes except for neonatal care unit admissions that were higher in newborns of women who were on labetalol compared to methyldopa.

Diabetes in pregnancy is known to increase the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes.15 Although there were significantly more women with diabetes who received methyldopa in our study (p = 0.038), this did not translate to higher adverse perinatal outcomes than women on labetalol. Extreme maternal age has also been shown previously to be an independent risk factor for adverse fetal outcomes.16 However, in our study, there was no significant difference in age between women who received labetalol or methyldopa. Therefore, the difference in the outcomes is unlikely to be attributed to maternal age or associated DM.

LBW, PTD, IUGR, SGA, respiratory distress syndrome, absent end diastolic flow, congenital defects, and neonatal care unit admission were significantly more prevalent in newborns of women who received combination therapy than newborns of women who were given a single medication. Preeclampsia, placental abruption, and HDU admissions were significantly more prevalent in women on combination therapy than women who received a single medication only. These women are more likely to have more severe uncontrolled hypertension that requires more antihypertensive medications, which may led to higher adverse perinatal, maternal, and fetal outcomes. However, this does not exclude the effect of medications that could have contributed to the increased adverse outcomes in these women. Coexisting comorbidities such as DM and maternal age might contribute to higher adverse outcomes; however, our study showed no significant difference between those on single and combined therapy in terms of mean age and DM.

The result of this study and previous similar

studies shall enhance the knowledge of the physicians to the perinatal outcomes associated with hypertension and antihypertensive medications, and to be more cautious when selecting and using antihypertensive medication in pregnant women. They should be more vigilant to the commonly reported outcomes during the antenatal and postnatal follow-up.

Conclusion

Preeclampsia was the most common type of hypertension, and labetalol was the most prescribed antihypertensive drug in our cohort. The majority of these patients were on combination therapy and associated with higher fetal and maternal outcome than women on single drug. Our study was conducted in a single specialized center therefore its findings cannot be generalized to women followed with general practitioners. For more robust conclusion, to determine whether these findings are attributed to the severity, chronicity, or antihypertensive medication, a further prospective study including groups of normotensive women and hypertensive women with and without medications in more than one specialized and primary health care center

is needed.

Disclosure

The author declared that the abstract of this study was presented in the Joint meeting of the European Society of Hypertension and International Society of Hypertension held in Glasgow, UK from April 11–14, 2021 and published in Journal of Hypertension 39, e342. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. Cooper RS, Kaufman JS, Bovet P. Global burden of disease attributable to hypertension. JAMA 2017 May;317(19):2017-2018.

- 2. Fuchs FD, Whelton PK. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 2020 Feb;75(2):285-292.

- 3. Thilaganathan B, Kalafat E. Cardiovascular system in preeclampsia and beyond. Hypertension 2019 Mar;73(3):522-531.

- 4. Scantlebury DC, Schwartz GL, Acquah LA, White WM, Moser M, Garovic VD. The treatment of hypertension during pregnancy: when should blood pressure medications be started? Curr Cardiol Rep 2013 Nov;15(11):412.

- 5. Fitton CA, Steiner MF, Aucott L, Pell JP, Mackay DF, Fleming M, et al. In-utero exposure to antihypertensive medication and neonatal and child health outcomes: a systematic review. J Hypertens 2017 Nov;35(11):2123-2137.

- 6. Pasker-de Jong PC, Zielhuis GA, van Gelder MM, Pellegrino A, Gabreëls FJ, Eskes TK. Antihypertensive treatment during pregnancy and functional development at primary school age in a historical cohort study. BJOG 2010 Aug;117(9):1080-1086.

- 7. Molvi SN, Mir S, Rana VS, Jabeen F, Malik AR. Role of antihypertensive therapy in mild to moderate pregnancy-induced hypertension: a prospective randomized study comparing labetalol with alpha methyldopa. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012 Jun;285(6):1553-1562.

- 8. Brown CM, Garovic VD. Drug treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. Drugs 2014 Mar;74(3):283-296.

- 9. Chan WS, Koren G, Barrera M, Rezvani M, Knittel-Keren D, Nulman I. Neurocognitive development of children following in-utero exposure to labetalol for maternal hypertension: a cohort study using a prospectively collected database. Hypertens Pregnancy 2010;29(3):271-283.

- 10. Roberts JM, August PA, Bakris G, Barton JR, Bernstein IM, Druzin M, et al. Hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013 Nov;122(5):1122-1131.

- 11. Subki AH, Algethami MR, Baabdullah WM, Alnefaie MN, Alzanbagi MA, Alsolami RM, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and fetal and maternal outcomes of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a retrospective study in western Saudi Arabia. Oman Med J 2018 Sep;33(5):409-415.

- 12. Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Burrows EA, Burrows RF. Use of antihypertensive medications in pregnancy and the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: McMaster outcome study of hypertension in pregnancy 2 (MOS HIP 2). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2001;1(1):6.

- 13. Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Ntumy MY, Obed SA, Seffah JD. Perinatal outcomes of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy at a tertiary hospital in Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017 Nov;17(1):388.

- 14. Pentareddy M, Dandge S. Effect of methyldopa and labetolol on fetal outcomes in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol 2017;6(12):2832.

- 15. Billionnet C, Mitanchez D, Weill A, Nizard J, Alla F, Hartemann A, et al. Gestational diabetes and adverse perinatal outcomes from 716,152 births in France in 2012. Diabetologia 2017 Apr;60(4):636-644.

- 16. Londero AP, Rossetti E, Pittini C, Cagnacci A, Driul L. Maternal age and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019 Jul;19(1):261.