On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 pandemic.1 Although not the worst pandemic known to humankind, the COVID-19 pandemic, which started in the Hubei province in China2 and later spread worldwide, has significantly impacted every industry. On 24 February 2020, Oman registered two COVID-19 cases for the first time following a return of travelers from Iran.3,4 The total registered cases on 12 April 2021 were 196 900 cases with 2053 deaths and 179 175 recovered cases.5,6 The highest reported COVID-19 cases in one day in Oman was 3544 cases on 11 April 2021.5 Due to the sharp increase of COVID-19 cases globally, the authorities imposed restrictions to prevent the spread of the disease. As in other countries, Oman also enforced lockdowns, the requirement to maintain social distance of at least 2 meters between individuals in all public and work areas, and the compulsory wearing of a mask.7–10 Furthermore, the ongoing pandemic impacted the educational institutions in many countries, including Oman, where schools, colleges, and universities either ended the academic year prematurely or evolved to remote learning measures to prioritize the needs to protect students and staff.11–13 The rapidly evolving changes resulted in multi-fold challenges in delivering academic knowledge and practical clinical skills to dental and medical students.14,15 In particular, clinical placements and clinical exposures required for students to progress in their studies were hindered by the abrupt halt in clinical contact hours required by the examination board and local and international authorities.16 Other contributing factors that negatively impacted clinical teaching were the lack of knowledge on best practices to control the spread of the virus, limited availability of personal protective equipments, the complexity in infection control measures related to clinical supervision in large-scale student dental clinical areas, and risks associated with aerosol generation of numerous dental procedures.16 An early study in the USA, at Roseman University of Health Sciences (RUHS) in College of Dental Medicine, evaluated students’ experience and perspectives of their academic institutions’ response to COVID-19.12 More than half of the participants reported accepting the overall response of the college to COVID-19, including effective online teaching, however, many students were dissatisfied with regards to the impact that the pandemic had on their clinical training.12

The pandemic has had academic, physiological, and psychological implications among students.17 Hung et al,12 reported the challenges that students faced in being able to focus on their studies and maintaining motivation to study. Furthermore, students reported having restless sleep, stress, anxiety related to the uncertainty of the pandemic, and anger due to feeling out of control. The dental students reported similar findings at the University of Jorden,18 where it was found that most of the students missed their clinical training sessions and were less motivated to learn online. However, the students reported that online sessions promoted group discussions amongst themselves and were satisfied with the level of preparedness of faculty at their university.

In Oman, there is a lack of studies that assessed the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare academic institutions as the demands on the students are very different from other non-patient-based professions. Some studies focused on the management of learning during the pandemic, including E-learning.19–21 However, a recent study reported the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among young students aged between 15 and 24 years in six Middle Eastern countries, including Oman.22 The study found that the participants’ prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress were 56.2%, 39.4%, and 31%, respectively. Unlike pre-COVID-19, the prevalence of depression and anxiety was 17%.23 The finding indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted the mental health of young participants. In addition, the prolonged lockdowns and restrictions have further contributions to this impact.22 However, none of the studies assessed the relationship between COVID-19 and students’ management of their healthcare dental education, in addition to the impact of the pandemic on their lifestyle. Therefore, the authors decided to use a survey to undertake this investigation to help Oman Dental College (ODC) to prepare and allocate adequate resources and better equip the college to meet its students’ specific demands as the timeline for the end of the pandemic remains uncertain. As ODC is a single-standing dental college, the first and only dental school in the Sultanate, it is safe to state that this kind of investigation is the first in Oman.

Methods

We designed a quantitative cross-sectional online survey study to identify ODC students’ management of their dental education during the COVID-19 pandemic and recognize the impact of the pandemic on student’s life.

We used the SurveyMonkey online tool24 to conduct the survey. The survey consisted of 11 general themes based on students’ opinions during the pandemic: (1) demographics, (2) associated risks of the COVID-19 pandemic, (3) sources of COVID-19 news, (4) the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their families, (5) application of hand hygiene measures, (6) the use of a facemask, (7) performance of exercise, (8) the college’s online services, (9) assignments, (10) faculty support, and (11) students’ mental health. Each theme had several items that were developed and subsequently independently reviewed by four interdisciplinary academic experts with backgrounds covering behavioral changes, adult restorative dentistry, and oral diseases. The survey questions/items were reviewed and refined by the researchers multiple times to enhance the validity of content and clarity from a student’s perspective and to reconfirm the face validity of the survey. There were some conflicts between the researchers; however, it was managed through the scientific criteria in designing the survey, including no leading and less biased questions and five-point options similar to Likert scales.25 The team looked whether each of the measuring items matches the given conceptual domain of the concept in the study. Few questions/items that did not meet the purpose of the survey were deleted, and finally, the expert consensus on the final version of the survey. Further, the students were exposed only to the items being questioned without the main themes to minimize any impact of selection bias. The survey has not been published in any scientific journal.

Predictive criterion validity was applied using a correlation coefficient. Construct convergent validity was performed by the team by comparing the questionnaire findings with their observation of students’ actions and attitudes. The outcome from this comparison helped make the necessary changes to the questionnaire. The four academic researchers reviewed all the questionnaire items for readability, clarity, and comprehensiveness. They came to some level of agreement as to include items that match their criteria in the final questionnaire. In addition, the experts reviewed the number of scales for each item. The construct and content validity process were done multiple times until the experts reached a consensus.

A sample frame is a source where the samples or list of samples are selected and recruited for a study.26 The sample frame for this study was conducted at ODC across all groups within one campus, located in Al Wattayah area, Muscat. ODC has a one-year foundation program (predental) and the Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) at ODC is a five-year program. The target sample population consisted of all the registered undergraduate dental students at ODC in the 2019–2020 academic year. The total number of target students were as follows: foundation year (FY), n = 61; first-year (BDSI), n = 65; second-year (BDSII), n = 70; third-year (BDSIII), n = 68; fourth-year (BDSIV), n = 64; and final year dental students (BDSV), n = 55. Due to limitations and constraints because of the pandemic, the sampling method was conducted by emailing the survey to all registered students; no particular group was selected. No power analysis was done because there was no sample size needed due to the limited population size.27

Ethical approval was obtained from the ODC Research and Ethics Committee (ODC Research 2020_2). An online written informed consent was obtained from each student following the perusal of an explanation of the research details. The survey link was circulated to all the registered students at ODC; students voluntarily opted to participate in the survey during a window of four weeks (email reminders were sent at the end of each week to gain more participations). On circulation of the link to the survey, a brief description of the survey was provided along with the confirmation that student participation was voluntary and anonymous. In addition, it was confirmed that any student opting not to participate in the survey, would not be negatively impacted in terms of his/her academic performance. Students were not offered any incentives to complete the survey.

The collected data was converted from the online SurveyMonkey to an excel spreadsheet and then exported to SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were applied to demographic and other characteristics of the participants’ data. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the internal consistency of the items relating to the eight themes of the online questionnaire: (1) associated risks of the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their families, (3) the use of a facemask, (4) performance of exercise, (5) the college’s online services, (6) assignments, (7) faculty support, and (8) students’ mental health. The overall mental health status of the students was calculated through computing with existing variables related to mental health. The normality tests were performed before any tests were done. A univariate analysis, which included nonparametric tests (not normally distributed data) and parametric tests (normally distributed data) was applied to identify the significant differences between genders and levels of study years with the eight themes of the questionnaire. The tests are in parametric test (independent t-test), non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney test), parametric test (analysis of variance (ANOVA)), and non-parametric test (Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA). Pearson’s correlation coefficient ‘r’ was used to evaluate the association between students’ perception of their risks of the COVID-19 pandemic and the other seven themes.

Results

Students of all study levels contributed to the survey; however, the response rate was 50.9% of the total number of registered students at ODC. Among the 195 students who contributed to the study, 91.8% (n = 177) were female and 8.2% (n = 16) were male. The majority of students were not married. Many respondents lived within Oman, and a limited number were international students. The majority of students were living with their families. Table 1 illustrates the details of the demographic data and the response rates.

Five of the themes showed internal reliability ranging from excellent to acceptable:

- Performance of exercise (0.51).

- The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their families (0.59).

- The use of a facemask (0.70).

- The college’s online services (0.78).

- Students’ mental health (0.90).

Risks of the COVID-19 pandemic, assignments, and faculty support were found to be below the level of acceptance (0.15, 0.24, and 0.35, respectively). Therefore, these three themes were excluded from the comparison or correlation analyses. Table 2 presents more details of Cronbach’s alpha for each theme.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of

the participants.

|

Academic year of study

|

|

|

|

Foundation year

|

13 (6.7)

|

3.4

|

|

First

|

26 (13.3)

|

6.8

|

|

Second

|

34 (17.4)

|

8.9

|

|

Third

|

51 (26.2)

|

13.3

|

|

Fourth

|

35 (17.9)

|

9.1

|

|

Final

|

36 (18.5)

|

9.4

|

|

Total

|

195 (100)

|

50.9

|

|

Gender

|

|

|

|

Male

|

16 (8.2)

|

|

|

Female

|

177 (91.8)

|

|

|

Marital status

|

|

|

|

Single

|

188 (96.4)

|

|

|

Married

|

7 (3.6)

|

|

|

Separated

|

|

0.0

|

|

Divorced

|

|

0.0

|

|

Widow

|

|

0.0

|

|

Widower

|

|

0.0

|

|

Do you have any children?

|

|

|

|

No

|

189 (97.4)

|

|

|

Yes, only one

|

3 (1.5)

|

|

|

Yes, two

|

2 (1.0)

|

|

|

Yes, three

|

0 (0.0)

|

0.0

|

|

Yes, four or more

|

0 (0.0)

|

0.0

|

|

Where do you live?

|

|

|

|

In Muscat governorate

|

91 (46.7)

|

|

|

Outside Muscat governorate

|

99 (50.8)

|

|

|

Outside Oman

|

5 (2.6)

|

|

|

Do you live?

|

|

|

|

Alone

|

3 (1.5)

|

|

|

With family

|

189 (96.9)

|

|

|

With friends

|

2 (1.0)

|

|

|

Other

|

1 (0.5)

|

|

|

Type of accommodation during the academic year

|

|

Single room occupancy in a student accommodation

|

12 (6.2)

|

|

|

Shared room occupancy in a student accommodation

|

54 (27.7)

|

|

|

Single occupancy private residence

|

6 (3.1)

|

|

|

Shared private residence

|

15 (7.7)

|

|

Some of the items were kept away from the above themes, either due to not matching other items, or they were extracted from a theme to raise the Cronbach’s alpha score.

Cronbach alpha score meaning: Excellent reliability (α ≥ 0.9); high reliability (0.7 ≤ α < 0.9); moderate reliability (0.5 ≤ α < 0.7); and low reliability (α < 0.5).28,29

More than half of the participants felt that the college encouraged them to engage in self-directed learning based on the available online resources. A high percentage of the students (80.4%, n = 156) attended online classes. The outcomes of the college’s online services were as follows:

1. Students believed that the classes were valuable 44.6% (n = 87), and the main reason for attending online classes was to keep up to date with the academic timetable (67.9%, n = 131).

2. In general, those students that attended the online classes felt that the quality and content of the online classes at ODC were good (51.0%, n = 99 and 41.0%, n = 80, respectively).

Table 2: Cronbach’s alpha for each theme related to the students’ perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

|

Risks of COVID-19 pandemic

|

6

|

0.15

|

25.7 ± 3.6

|

|

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their families

|

2

|

0.59

|

8.7 ± 1.1

|

|

The use of a facemask

|

2

|

0.70

|

8.5 ± 1.4

|

|

Performance of exercise

|

2

|

0.51

|

6.7 ± 3.8

|

|

The college’s online services

|

9

|

0.78

|

40 ± 5.8

|

|

Assignments

|

3

|

0.24

|

8.2 ± 1.7

|

|

Faculty support

|

3

|

0.35

|

8.7 ± 2.1

|

However, 45.9% (n = 89) of students felt that their remote teaching sessions experience was worse than onsite lectures.

3. A large number of students (72.3%, n = 141) felt they missed out on critical education, which could impact their academic progression.

Overall, BDS students were satisfied with the college’s online services [Figure 1]. Table 3 details the responses of each item related to the college’s online services theme.

Around 70% (n = 136) of the students preferred open-book assignments (OBAs) over other types of assessments. However, 62.1% (n = 121) of participants expressed they experienced difficulty with OBAs and found it to be challenging, although 45.9% (n = 89) of students were indifferent to the OBAs they undertook in ODC versus the standard mode of assessment/examination [Table 3].

.png) Figure 1: Overall satisfaction level of online

Figure 1: Overall satisfaction level of online

college services.

Table 3: Students’ responses on the college's online services.

|

College is encouraging students to engage in self-directed learning based on the available online resources

|

Encourage

|

100 (51.5)

|

194

|

|

Attendance of the online classes

|

Attending

|

156 (80.4)

|

194

|

|

Reason for attending the online lectures

|

Keeping in touch with the academic timetable

|

131 (67.9)

|

193

|

|

Helpfulness of online teaching to keep up with students’ timetabled academic schedules

|

Helpful

|

116 (59.5)

|

195

|

|

Valuable of the online teaching at ODC**

|

Valuable

|

87 (44.6)

|

195

|

|

Quality of the online class content at ODC

|

Good

|

99 (51.0)

|

194

|

|

Satisfaction with the content of the online lectures

|

Satisfied

|

80 (41.0)

|

195

|

|

Missing out on critical education affects students’ academic progression because of online learning

|

Yes

|

141 (72.3)

|

195

|

|

Comparison between the remote online teaching content and the campus teaching

|

Somewhat worse the physical lectures

|

89 (45.9)

|

194

|

|

Assignments

|

|

Preference for open-book assignments over other types of assessments

|

Preferred

|

136 (69.7)

|

195

|

|

Difficulties with respect to open-book assignments

|

Difficult

|

121 (62.1)

|

195

|

|

The college planned well for future examinations

|

Neutral

|

89 (45.9)

|

194

|

|

Faculty support

|

|

Ease for students to reach out to the academic faculty for help

|

Neutral

|

108 (55.4)

|

195

|

|

Connected with the college in terms of learning

|

Connected

|

95 (49.0)

|

194

|

|

Effect of college suspension on clinical education

|

Affected

|

121 (62.7)

|

195

|

|

Mental health , in the past 14 days of onsite suspension

|

|

Fearful, anxious, or worrisome emotions

|

Always

|

104 (53.3)

|

195

|

|

Stress

|

Always

|

109 (55.9)

|

195

|

|

Focusing on anything other than anxiety, nervousness, or tension

|

Always

|

94 (48.2)

|

195

|

|

Sleeping pattern

|

Sleep more

|

109 (55.9)

|

195

|

|

Feeling more irritated, grouchy, or angry than usual**

|

Never

|

68 (35.1)

|

194

|

|

Feeling irritable or have angry outbursts**

|

Not at all

|

105 (53.8)

|

195

|

|

Feeling nervous or worried

|

Sometimes nervous and worried

|

71 (36.4)

|

195

|

|

Feeling frightened

|

Never frightened

|

83 (42.6)

|

195

|

|

Having difficulty concentrating

|

Sometimes

|

77 (39.5)

|

195

|

|

Interest in doing things

|

Interest

|

110 (56.4)

|

195

|

|

Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless

|

Always

|

82 (42.1)

|

195

|

|

Having unexplained body aches and pains

|

1–2 days a week

|

77 (39.5)

|

195

|

|

Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of a stressful experience

|

Not at all

|

79 (40.5)

|

195

|

|

Feeling upset when a stressful experience is reminded**

|

Not at all

|

75 (38.5)

|

195

|

|

Sometimes

|

75 (38.5)

|

|

|

Pandemic effects on relationships

|

Not affected

|

114 (58.5)

|

195

|

|

Feeling distant, lonely, or cut off from other people

|

Not at all

|

79 (40.5)

|

195

|

|

Having thoughts of actually hurting oneself

|

Not at All

|

168 (86.6)

|

|

ODC: Oman Dental College.

*The options mentioned in the table are the most selected response among the participants.

**The item has two equal ratings.

Almost half of the students (49.0%, n = 95) felt connected with the college regarding their learning experience, and 55.4% (n = 108) confirmed that it was neither easy nor difficult to reach out to the faculty for academic help and support. However, 62.1% (n = 121) of the students felt that the college’s suspension of clinical education (imposed by the local authorities) affected them negatively [Table 3].

More than 93.0% (n = 182) of the students reported that none of their family members had suffered from COVID-19. Around 71.0%

(n = 138) of the students wore facemasks when they were outside their homes before it became compulsory, and 62.4% (n = 121) of the students confirmed that they strongly believed in the importance of wearing a mask.

Only a limited number of students performed exercise before and during the pandemic, 4.6% (n = 9) and 10.8% (n = 21), respectively. The majority of the students did not perform any exercise, and there was not much difference in their exercise activity either before or during the COVID-19 pandemic (39.2%, n = 76 and 34.0%, n = 66, respectively).

More than half of the students felt nervous, worried, anxious, or tensed and stressed within the first 14 days of college lockdown due to COVID-19. Fortunately, despite these negative feelings, 48.2% (n = 94) of students could focus on other things rather than the negative feelings and 56.4% (n = 110) could do interesting things. Although 35.1% (n = 68) of students did not feel more irritated, grouchy, or angry than usual, 42.1% (n = 82) felt down, depressed, or hopeless and about 36.4% (n = 71) of students were sometimes nervous and worried.

Moreover, 55.9% (n = 109) slept more than usual and up to 39.5% (n = 77) had unexplained body aches and pains 1–2 days a week. In relation to feeling upset due to stressful experience, 38.5% (n = 75) of the students felt upset and 38.5% (n = 75) did not feel upset. Moreover, 39.5% (n = 77) expressed difficulty in concentration at times.

Nevertheless, 42.6% (n = 83) never felt frightened, and 40.5% (n = 79) did not have repeated disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of a stressful experience nor felt distant, lonely, or cut off from other people. More than half (53.8%, n = 105) of the participants did not feel irritable or have angry outbursts. Most of the participants (86.6%, n = 168) did not have thoughts of hurting themselves, and 70.1% (n = 136) of the students did not require the use of painkillers, stimulants, sedatives, or tranquilizers without a doctor’s prescription. Finally, 58.5% (n = 114) felt that the pandemic did not affect their relationship with other people [Table 3].

The indicators of the ODC students’ mental health status are presented in Table 3. It is evident that in the first two weeks of suspended onsite activities, many students experienced some fear/anxiety (53.3%, n = 104) and stress (55.9%, n = 109), which impacted their ability to focus on other matters in life (48.2%, n = 94). Following the first two weeks of suspension of onsite activities within ODC, it was evident that students slept more than usual (55.9%), interestingly enough, although 39.5% of students found it hard to concentrate, 56.4% of students did not lose interest in doing things. However, the overall students’ mental health experience during the last academic year was healthy, as indicated in Figure 2.

.png) Figure 2: The general mental health status among the Bachelor of Dental Surgery students.

Figure 2: The general mental health status among the Bachelor of Dental Surgery students.

There were statistical differences between levels of study in the college’s online services (p < 0.001) and the students’ mental health (p < 0.03).

BDSIV scored the highest in the college’s online services satisfaction (34.3±5.3) compared with the other BDS levels. Also, they scored the highest in students’ mental health (63.5±12.6), which indicates that they were the most healthy group among all BDS levels. BDSII scored the lowest in the college’s online services satisfaction (27.1±4.9). BDSI scored the lowest in students’ mental health (52.8±10.4), which indicates that they were the least healthy group among all BDS levels. There was no statistical difference in the performance of exercise, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their families, and the use of facemask themes among the BSD levels of study themes. Table 4 presents details of the differences between the academic year of study with the themes.

There were no statistical differences between females and males in the five themes. Table 5 presents details of the difference between gender in the themes.

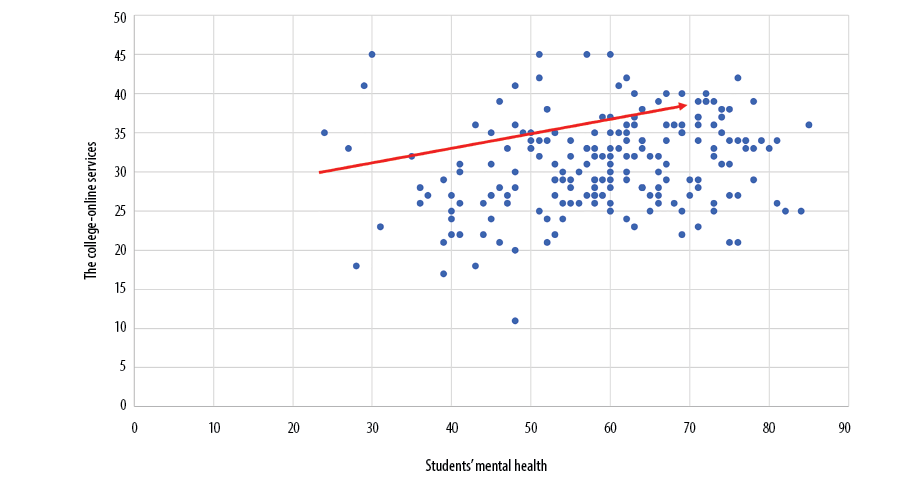

The college’s online services satisfaction during the pandemic theme was positively related to the students’ mental health (r = 0.22, p < 0.001) [Figure 3]. The more students are satisfied with the online college service, the more mental health will be positive. The other themes were not significantly related to the students’ mental health during the pandemic. The detailed results of the correlation between students’ mental health during the pandemic and other themes are shown in Table 6.

Table 4: The differences between the academic year of study in relation to the themes.

|

Performance of exercise*

|

|

FY

|

13

|

7.0 ± 3.7

|

0.97

|

|

BDSI

|

25

|

6.5 ± 3.2

|

|

|

BDSII

|

34

|

6.9 ± 4.4

|

|

|

BDSIII

|

51

|

6.3 ± 3.7

|

|

|

BDSIV

|

35

|

6.5 ± 3.4

|

|

|

BDSV

|

36

|

6.8 ± 3.9

|

|

|

The college’s online services*

|

|

FY

|

13

|

33.3 ± 4.5

|

< 0.001

|

|

BDSI

|

26

|

28.1 ± 6.4

|

|

|

BDSII

|

34

|

27.1 ± 4.9

|

|

|

BDSIII

|

51

|

30.9 ± 5.8

|

|

|

BDSIV

|

35

|

34.3 ± 5.3

|

|

|

BDSV

|

36

|

32.0 ± 4.5

|

|

|

Students’ mental health*

|

|

FY

|

13

|

60.0 ± 10.3

|

0.03

|

|

BDSI

|

26

|

52.8 ± 10.4

|

|

|

BDSII

|

34

|

56.8 ± 12.0

|

|

|

BDSIII

|

51

|

60.3 ± 12.3

|

|

|

BDSIV

|

35

|

63.5 ± 12.6

|

|

|

BDSV

|

36

|

59.4 ± 14.0

|

|

|

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their families**

|

|

Total

|

195

|

8.4 ± 1.8

|

0.35

|

|

The use of facemask**

|

ODC: Oman Dental College; FY: foundation year; BDSI: Bachelor of Dental Surgery fisrt-year ; BDSII: second-year; BDSIII: third-year; BDSIV: fourth year; BDSV: final year.

*Parametric test analysis of variance (ANOVA).

**Non-parametric test Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA.

Table 5: The differences between genders in relation to the themes.

|

The college’s online services*

|

|

Male

|

16

|

30.7 ± 7.4

|

0.91

|

|

Female

|

177

|

30.9 ± 5.6

|

|

|

Students’ mental health*

|

|

Male

|

16

|

60.6 ± 14.0

|

0.67

|

|

Female

|

177

|

59.2 ± 12.3

|

|

|

The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on their families**

|

|

Total

|

195

|

8.4 ± 1.8

|

0.78

|

|

The use of facemask**

|

|

Total

|

195

|

8.4 ± 1.4

|

0.27

|

|

Performance of exercise**

|

*Parametric test independent test.

**Non-parametric test Mann-Whitney test.

Figure 3: The significant positive weak relation between Oman Dental College-online service and students’ mental health.

Figure 3: The significant positive weak relation between Oman Dental College-online service and students’ mental health.

Table 6: The correlation between students’ mental health and other themes.

|

Students’ mental health

|

59.1 ± 12.5

|

0.09 (0.23)

|

0.0081

|

weak/small

|

|

The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on their families

|

8.3 ± 1.8

|

|

|

|

|

Students’ mental health

|

59.1 ± 12.5

|

0.07 (0.33)

|

0.0049

|

weak/small

|

|

The use of facemask

|

8.4 ± 1.4

|

|

|

|

|

Students’ mental health

|

59.1 ± 12.5

|

0.12 (0.11)

|

0.0144

|

weak/small

|

|

Performance of exercise

|

6.6 ± 3.7

|

|

|

|

|

Students’ mental health

|

59.1 ± 12.5

|

0.22 (< 0.001)

|

0.0484

|

weak/small

|

Discussion

This online cross-sectional study aimed to explore the perceptions of ODC students on ODC’s management of their dental education during the COVID-19 pandemic. In adddition, it recognized the impact of the current pandemic on the students’ life. The COVID-19 pandemic caused many schools and universities to temporarily suspend onsite activities and adopt different strategies to ensure the continuity of the learning process.12

In this survey, most of the BDS students contributed, however, the foundation year students contributed the least. Being new in the college and limited activities due to COVID-19 could be attributed to the reduced participation in the survey. Many students were positive about the online services provided by ODC; they described them as valuable, the faculty members were supportive and encouraging, and the teaching was also described as good quality. Although ODC students expressed satisfaction about online teaching, they raised concerns about missing critical components of their education. Many students expressed that online teaching was slightly inferior to onsite teaching experiences. Similar findings were reported by Hung et al,12 many dental students at the RUHS College of Dental Medicine reported effective and positive experiences with the online services and their academic professors. However, over one-third of the RUHS students raised concern over the quality of online teaching. ODC students felt they were connected to faculty in terms of learning and a limited number of them expressed some difficulties in getting in touch with faculty. These difficulties may be related to the technicalities of the internet network services in their geographical location or perhaps due to the negative impact of the pandemic on their physical and emotional well-being.

In relation to the clinical aspects of education, many ODC students raised concerns about the college suspension of onsite clinical activities and its impact on their training and clinical experience. Clearly, the suspension of clinical activity was a crucial protective measure for all the ODC stakeholders. The ODC findings were similar to those reported in RUHS.12 These negative outcomes in the two studies indicate the helplessness of students in the decisions being made by the authorities. Furthermore, the lack of involvement in understanding the thought process behind the decisions being made may have exacerbated the negative feelings expressed by the students. Involving students in decision-making gives them ownership and a sense of control. In addition, students’ input in clinical education options such as utilizing online demonstration and exploring simulation can further positively impact their clinical training and perhaps result in less negative survey outcomes.

Regarding assessments, more than half of the ODC students preferred introducing OBAs. However, many of them expressed difficulty completing the assignments. This perhaps is a point for ODC’s assessment team to consider inviting students to express their challenges for the assessment team to review and evaluate potential solutions. It is worth noting, however, that the foundation year students and those that entered BDSI would not be able to compare the OBA experience in a meaningful manner.

The majority of ODC students reported that none of their families contracted COVID-19 at the time the survey was undertaken (15 June 2020). Similar findings were reported by Al Omari et al,22 across six different Arab countries, including Oman. More than 62.0% of the ODC students supported wearing facemasks in public places, and two-thirds of them were wearing facemasks before it became mandatory. This reflects students’ awareness of the importance of wearing facemasks in minimizing the spread of infectious diseases in the community. The RUHS students reported the importance of wearing facemasks during the pandemic in public places.12

The majority of the ODC students did not exercise every day. This may have contributed to some mental health issues amongst the students. Cumulative evidence indicated that exercise helps improve sleep quality and mental health, including reducing the risk of depressive illness.30–34 Therefore, raising awareness of the importance of exercise on mental health among the students would help to increase their physical activity.35

The pandemic negatively affected many college students leading them to experience a certain degree of anxiety, stress, depression, and sleeping pattern.12,17,22 Within the 14 days of lockdown, many ODC students were fearful, anxious, worried, stressed, feeling down, depressed, and hopeless, and many slept more than usual. This has negatively impacted their sleeping pattern, in which the majority had disturbed sleeping patterns ranging from less to high hours of sleeping. However, after 14 days, the level of nervousness, worry, and stress dropped to having difficulty in concentration; this could be attributed to the adaptation and application of different coping strategies, as advocated by the World Health Organization.35 Although the students experienced some mental health issues within the first 14 days, they could focus on other matters after that. In addition, they did not experience irritation, getting grouchy, or being angry to an extent that was more than usual. Neither did they get frightened or experience disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of a stressful experience. Fortunately, none of them had thoughts of hurting themselves or needed to take painkillers, stimulants, sedatives, or tranquilizers without a doctor’s prescription. It is worth noting that many students never experienced loneliness, and the pandemic did not impact their relationships. However, it is worth highlighting that although the number of cases in Oman had started to increase, the magnitude of this rise was not as large as in other geographical locations. For instance, in June 2020, the number of recorded COVID-19 cases in Saudi Arabia and Iran exceeded 100 000 cases, unlike the number of cases recorded in Oman, which was below 30 000 cases.37 The study of Al Omari et al,22 found that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among the participants in Oman was 56.2%, 39.4%, and 31%, respectively, which is similar to the findings of the current study. The RUHS students, on the other hand, reported loneliness due to low social connections and high-stress levels associated with worsening their health behavior.12 Perhaps the difference between RUHS and ODC students is indirectly impacted by their cultural and environmental backgrounds. This means that students across different backgrounds experienced mental issues of different magnitudes during COVID-19.

For decision-making at ODC, it was important to identify any differences between the BDS study levels to establish the proper interventions for each group. This study identified statistical differences between BDS levels of study in the college’s online teaching services during the pandemic and the ODC students’ mental health issues. In other words, at each level, BDS students interacted differently with the online services resulting in different mental health statuses. For example, BDSIV students were the most satisfied group in utilizing the college’s online services (mean = 34.3), and they were the group with the least mental health issues (mean = 63.5). However, BDSII students were the least satisfied group while utilizing the college’s online services (mean = 27.1), and they had more mental health issues (mean = 56.8) than the BDSIV students. The differences in the college’s online teaching services and mental health issues among BDS levels of study may be explained by the different experiences of each group of students within the college environment. For instance, foundation year students were more satisfied with the online service when compared with the BDSI students. This difference could be because foundation year students were in their first-time experience in the college environment and possibly felt that the college managed the COVID-19 crisis effectively, resulting in a healthy mental status, unlike BDSI students. Another possible explanation could be the implementation of the COVID-19 management system by the college without meeting the needs of each BDS academic level or consulting the students in curriculum management. Therefore, the findings suggest that it is important to consider students’ opinions or meet their needs when managing any crisis related to dental education was emphasized by Geraghty et al,38 and AlHamdan et al.39 They suggested that involving students’ feedback in the designing of curriculum (e.g., delivery of sessions) would increase students involvement in the learning process. This ultimately would increase their satisfaction and healthy mental status. Our study is the first to report the differences between the BDS levels of study. This study assessed the difference between males and females in all five themes including mental health issues. The findings of this study are similar to the findings of Cao et al,17 in China, where no difference was found between males and females in all five themes including mental health issues.

The ODC online services during the pandemic theme are positively related to the students’ mental health during that time. This means that the online lectures significantly impacted the students’ mental health issues. One of the possible explanations for this finding is that the college’s online strategy helped reduce mental health issues among the BDSIV students. This echoes the finding of Hilliard et al,40 that many students felt a reduction in anxiety levels during online learning. Furthermore, the college gradually shifted from physical learning to online learning, which helped reduce the anxiety and stress levels of the students who used the services. Fawaz and Samaha emphasized that the sudden shift to online learning could lead to anxiety and depression among the students.41 This is the first study to report this association, emphasizing the positive association between the satisfaction of online services during the pandemic and students’ mental health status.

This study is limited to a small number of dental students from ODC and it is based on the convenience sampling method. In addition, the majority (91.7%) of the participants were female dental students, which does not represent the college population. Some of the themes in the questionnaire had poor internal consistency scores resulting in their exclusion from the comparison or correlation analysis. Moreover, the findings from this study could be outdated since pandemic management continues to evolve. Nonetheless, the results can be a fair representation of the experience of dental students from all levels of study. Future studies may be undertaken to compare different dental schools at the regional level and with good Cronbach alpha scores to themes relating to students’ attitude/perception about ODC’s assignments during the COVID-19 pandemic; and the students’ attitude/perception about the support offered by ODC faculty during the pandemic.

Conclusion

COVID-19 affected many college students internationally and locally, including ODC students. Our study findings indicate that ODC students were experiencing certain mental health-related issues caused by COVID-19, which included anxiety, stress, and sleeping patterns. Most of the students appeared to be satisfied with the online teaching provided by the college, and the faculty were connected with the students most of the time.

However, students were not comfortable with the management of clinical education and expressed difficulty with regard to the OBAs. We found a positive relationship between the management of online lectures and students’ mental health. These findings could appraise the management of educational institutions in making academic decisions, especially concerning clinical practice included in dental and medical programs. Such information may also help other educational institutions like ODC to prepare and allocate resources to support their students in the future as needed.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

references

- 1. WHO. Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19: 11th March 2020. [cited 2020 March 30]. Available from: https://www. who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the- media-briefing-on-covid-19—20-march-2020.

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020 Feb;395(10223):497-506.

- 3. WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Oman. 2020 [cited 2020 November 6]. Available from: https://who.sprinklr.com/region/emro/country/om.

- 4. Ministry of Health. Oman. Statements and updates corona virus disease (COVID-19), 2020 [cited 2020 November 6]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.om/en/-59.

- 5. WHO. COVID-19 Oman. 2020 [cited 2020 May 4]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/emro/country/om.

- 6. Worldometer. COVID-19 Oman. 2021 [cited 2020 May 4]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/oman/.

- 7. ECDE. Guidelines for non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in the EU/EEA and the UK. ECDC: Stockholm;2020.

- 8. Han E, Tan MM, Turk E, Sridhar D, Leung GM, Shibuya K, et al. Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: an analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. Lancet 2020 Nov;396(10261):1525-1534.

- 9. Supreme Committee on Covid-19. The supreme committee in charge of discussing a mechanism for dealing with developments resulting from the spread of the Coronavirus (Covid 19) holds its second meeting. 2020 [cited 2020 May 5]. Available from: https://omannews.gov.om/Oman-News-Agency/ArtMID/458/ArticleID/10233.

- 10. Supreme Committee on Covid-19. The supreme committee issues new decisions. 2020 [cited 2020 May 5]. Available from: https://www.atheer.om/archives/520034/%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%84%d8%ac%d9%86%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%84%d9%8a%d8%a7-%d8%aa%d8%b5%d8%af%d8%b1-%d9%82%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%ac%d8%af%d9%8a%d8%af%d8%a9/.

- 11. UNESCO. COVID-19 impact on education. 2019 [cited 2020 November 7]. Available from: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse.

- 12. Hung M, Licari FW, Hon ES, Lauren E, Su S, Birmingham WC, et al. In an era of uncertainty: impact of COVID-19 on dental education. J Dent Educ 2021 Feb;85(2):148-156.

- 13. MoHERI. Statement of Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation to suspend private and government universities, colleges. 2020 [cited 2020 May 5]. Available from: tweeter account: https://twitter.com/omanmohe/status/1238866004542984192/photo/1.

- 14. Guadix SW, Winston GM, Chae JK, Haghdel A, Chen J, Younus I, et al. Medical student concerns relating to neurosurgery education during COVID-19. World Neurosurg 2020 Jul;139:e836-e847.

- 15. Khalafallah AM, Jimenez AE, Lee RP, Weingart JD, Theodore N, Cohen AR, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on an academic neurosurgery department: The Johns Hopkins experience. World Neurosurg 2020 Jul;139:e877-e884.

- 16. Barabari P, Moharamzadeh K. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and dentistry—a comprehensive review of literature. Dent J (Basel) 2020 May;8(2):E53.

- 17. Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 2020 May;287:112934.

- 18. Hattar S, AlHadidi A, Sawair FA, Abd Alraheam I, El-Ma’aita A, Wahab FK. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on dental academia. Students’ experience in online education and expectations for a predictable practice. Research Square; 2020.

- 19. Almaiah MA, Al-Khasawneh A, Althunibat A. Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic.Educ Inf Technol (Dordr) 2020;1-20.

- 20. Mohmmed AO, Khidhir BA, Nazeer A, Vijayan VJ. Emergency remote teaching during Coronavirus pandemic: the current trend and future directive at Middle East College Oman. Innov Infrastruct Solut 2020;5(3):72.

- 21. Syahrin, Salih. An ESL online classroom experience in Oman during Covid-19. Arab World English Journal 2020;11(3):42-55.

- 22. Al Omari O, Al Sabei S, Al Rawajfah O, Abu Sharour L, Aljohani K, Alomari K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress among youth at the time of COVID-19: an online cross-sectional multicountry study. Depress Res Treat 2020 Oct;2020:8887727.

- 23. Afifi M, Al Riyami A, Morsi M, Al Kharusil H. Depressive symptoms among high school adolescents in Oman. East Mediterr Health J 2006;12(Suppl 2):S126-S137.

- 24. Momentive. SurveyMonkey. 2020 [cited 2020 May 5]. Available from: https://help.surveymonkey.com/en/.

- 25. Oberski DL. Questionnaire science. Atkeson and Alvarez, editors. Introduction to polling and survey methods. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 113-140.

- 26. Ritchie J, Lewis J, El Am G. Designing and selecting samples. In Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers, Sage Publication, London. 2003. p. 77-108.

- 27. Kotu V, Deshpande B. Predictive analytics and data mining: concepts and practice with rapidMiner. Elsevier: Waltham, MA; 2015.

- Hinton P, Brownlow C, McMurray I, Cozens B. SPSS explained Routledge. 2004.

- Hinton, P. R., McMurray, I., & Brownlow, C. (2014). SPSS explained (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- 28. Alexandratos K, Barnett F, Thomas Y. The impact of exercise on the mental health and quality of life of people with severe mental illness: a critical review. Br J Occup Ther 2012;75(2):48-60.

- 29. Stanton R, Happell B, Reaburn P. The mental health benefits of regular physical activity, and its role in preventing future depressive illness. Nursing (Auckl) 2014;4:45-53.

- 30. Lubans D, Richards J, Hillman C, Faulkner G, Beauchamp M, Nilsson M, et al. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: a systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016 Sep;138(3):e20161642.

- 31. Hu MX, Turner D, Generaal E, Bos D, Ikram MK, Ikram MA, et al. Exercise interventions for the prevention of depression: a systematic review of meta-analyses. BMC Public Health 2020 Aug;20(1):1255.

- 32. Wang F, Boros S. The effect of physical activity on sleep quality: a systematic review. Eur J Physiother 2021;23(1):11-18.

- 33. WHO motion for your mind: physical activity for mental health promotion, protective and care. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019.

- 34. WHO. Doing what matters in times of stress: an illustrated guide. World Health Organization; 2020.

- 35. WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report – 153 data as received by WHO from national authorities by 10:00 CEST, 21 June 2020.

- 36. Geraghty JR, Young AN, Berkel TD, Wallbruch E, Mann J, Park YS, et al. Empowering medical students as agents of curricular change: a value-added approach to student engagement in medical education. Perspect Med Educ 2020 Feb;9(1):60-65.

- 37. AlHamdan EM, Tulbah HI, Alduhayan GA, Albedaiwi LS. Preferences of dental students towards teaching strategies in two major dental colleges in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Educ Res Int 2016;4178471.

- 38. Hilliard J, Kear K, Donelan H, Heaney C. Students’ experiences of anxiety in an assessed, online, collaborative project. Comput Educ 2020;143:103675.

- 39. Fawaz M, Samaha A. E-learning: depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology among Lebanese university students during COVID-19 quarantine. Nurs Forum 2021 Jan;56(1):52-57.