Wilson’s disease is attributed to a mutation in the ATP7B gene on chromosome 13 which causes an error in copper metabolism. The ATP7B protein is involved in the incorporation of copper into ceruloplasmin and its transport into the bile.1 Neurologic dysfunction is the initial clinical manifestation of Wilson’s disease in 40–60% of patients, with usual appearance at around 20 years of age, while initial hepatic manifestations are seen in 40–50% of patients with a slightly earlier age of onset.2,3 Wilson’s disease with its varied clinical manifestations is a diagnostic challenge. Seizure is uncommon in Wilson’s disease and its initial presentation as seizure is very rare.

Case Report

A 17-year-old male was admitted with recurrent episodes of seizures. The patient had a low-grade fever for two days, a week prior to admission. He started to have visual hallucinations in the form of seeing things burning at a distance. On the night prior to admission, his parents heard a loud cry from his room and found him convulsing and he had six serial seizures. He was diagnosed as a case of acute encephalopathy with seizures and managed as status epilepticus.

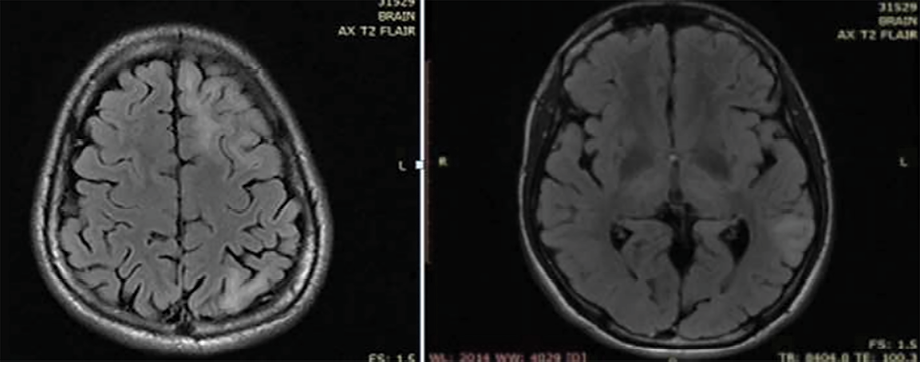

The patient was evaluated for infectious and autoimmune causes for his condition. His cerebrospinal fluid study yielded normal results; cerebrospinal fluid viral markers were negative for herpes simplex 1 and 2 and varicella zoster. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody was negative. He was given a course of acyclovir and methylprednisolone, followed by oral steroids. Though the patient made a gradual recovery in one week, he remained stubborn and irritable. Upon recovery, he was clinically normal without any neurologic deficits. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed multiple cortical hyperintensities and subcortical white matter hyperintensities [Figure 1]. Interictal electroencephalogram showed focal epileptiform discharges from the left frontal region.

Figure 1: MRI of the brain showing multiple cortical and subcortical white matter hyperintensities.

Figure 1: MRI of the brain showing multiple cortical and subcortical white matter hyperintensities.

The patient was discharged on steroids and sodium valproate as an antiepileptic. At the four-month follow-up visit to the neurology clinic, asymmetric tremors of the hands and dysarthria were noticed. Initially, this was suspected to be post encephalitis sequelae or due to drug effect. He was started on levodopa and trihexyphenidyl with which he made a mild improvement.

Five months after the first admission, the patient, who had been compliant with the prescribed medications and his steroid was being tapered, was readmitted with recurrent seizures. The seizure episodes were characterized by behavioral arrest, head aversion to the right, and drooling of saliva that lasted about a minute.

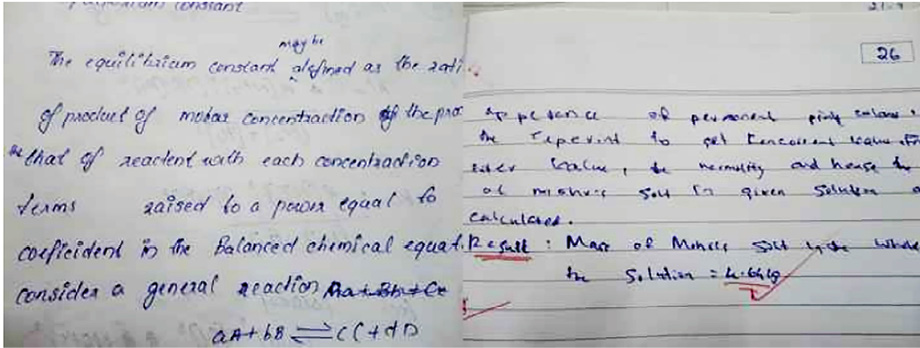

The patient was readmitted and his parents were again interviewed for any relevant past history. They revealed a slow decline in his school performance during the previous year, and that his handwriting had become much less legible [Figure 2]. There was no relevant family history. His parents were non-consanguineous.

Figure 2: Handwriting sample before symptoms (left). Handwriting after one year, showing a decline in legibility (right).

Figure 2: Handwriting sample before symptoms (left). Handwriting after one year, showing a decline in legibility (right).

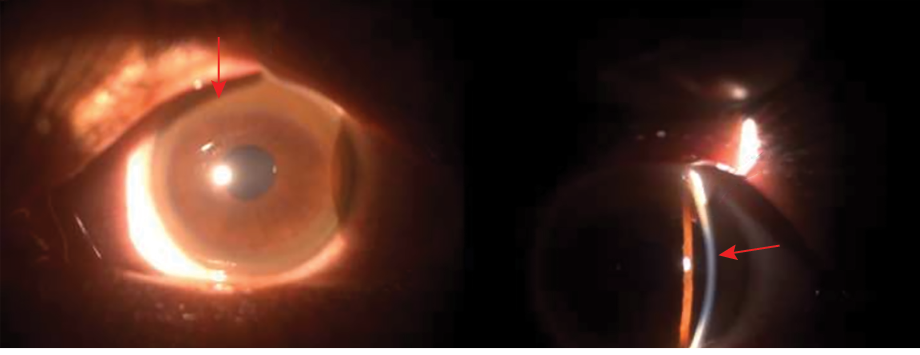

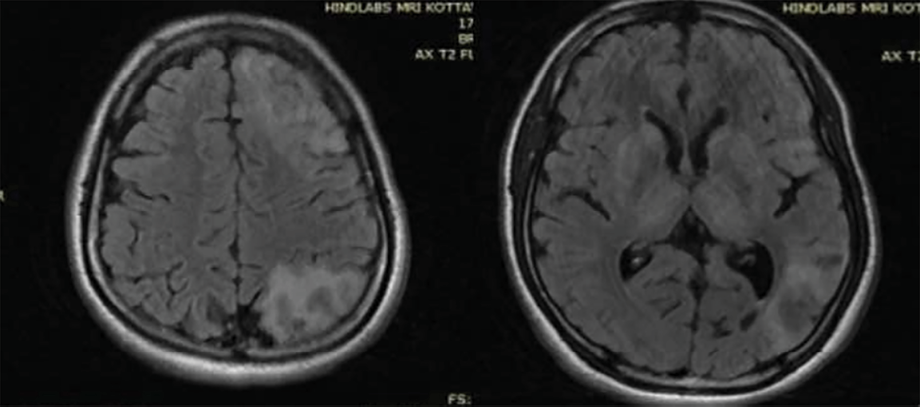

In view of the unusual presentation of mild parkinsonian symptoms and tremors in a young patient, he was reexamined thoroughly. Slit lamp examination of the eyes showed Kayser-Fleischer rings [Figure 3]. Serum ceruloplasmin level was 3 mg/dL (in Wilson’s disease it is < 20 mg/dL) and the copper content in 24-hour urine output was 103 mcg (> 100 mcg is diagnostic of Wilson’s disease). Liver function test showed mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase. Blood coagulation level was normal while hemoglobin was low (10 g/dL). Peripheral blood smear test yielded normal results. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed hyperechoic liver parenchyma and no cirrhosis. A follow-up MRI of the brain showed T2 hyperintensities in subcortical white matter, symmetric hyperintensities in the caudate, putamen, and thalamus [Figure 4].

Figure 3: Slit lamp photograph of the patient’s eye showing Kayser- Fleisher ring (red arrows).

Figure 3: Slit lamp photograph of the patient’s eye showing Kayser- Fleisher ring (red arrows).

Figure 4: Follow-up MRI brain after six months showing T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities in white matter, as well as hyperintense lesions in bilateral basal ganglia and thalamus.

Figure 4: Follow-up MRI brain after six months showing T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities in white matter, as well as hyperintense lesions in bilateral basal ganglia and thalamus.

Based on these results, Wilson’s disease was confirmed in this patient. He was initially treated with zinc sulfate and then started on penicillamine with slow up-titration of the dose. As tremor and parkinsonian symptoms resolved, the antiepileptic doses were tapered to minimum. Currently (after six months of discharge), he is stable without recurrence of neurologic symptoms and is compliant with the prescribed long-term medications.

Discussion

In Wilson’s disease, the major neurological symptoms are extrapyramidal, the usual ones being tremors, dystonia, parkinsonism, dysphagia, and dysarthria. Chorea, athetosis, and myoclonus can also occur albeit rarely.4,5 Cerebellar dysfunction develops in approximately 30% of patients.6 Initial presentation of acute encephalopathy with seizures is rare. Only 8% of patients with Wilson's disease have seizures, 20% of whom would have had seizures before the onset of the characteristic features of Wilson’s disease.7 Such seizures can be simple, complex, partial, generalized tonic-clonic (the commonest form), secondary generalized, periodic myoclonus, or status epilepticus.7–9

The prognosis of seizures in Wilson’s disease is positive, being rarely refractory. MRI imaging characteristics in Wilson’s disease patients with seizures were similar to those without seizures.7 Seizure outcome is perhaps independent of the type of anti-epileptic drug used. There is no specific guideline as to which anti-epileptic drug is preferable.

The most characteristic abnormalities in Wilson’s disease are increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images and reduced signal intensity on T1-weighted images in the basal ganglia, brainstem, and thalamus.10 The ‘face of the giant panda sign’ in the midbrain, the ‘face of the miniature panda sign’ in the pons, and the bright claustrum sign, while described, occur only rarely and thus are of limited diagnostic value. White matter signal changes can also be seen in Wilson’s disease. The presence of subcortical white matter lesion, particularly the frontal lobe, is correlated with seizure.7 Seizures can occur at any stage of Wilson’s disease—as the first symptom, at the initiation of treatment, during treatment, or as a terminal event. Electroencephalogram abnormalities include generalized and focal epileptiform discharge, diffuse or focal slowing of background activity, or periodic high voltage activity.7 The possible mechanisms for seizure in Wilson’s disease include direct toxicity from accumulated free copper, pyridoxine deficiency due to penicillamine treatment, or metabolic encephalopathy.6,11

Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms are common in Wilson’s disease and may precede other symptoms. This may be in the form of declining school performance, impulsiveness, or psychotic features. Severe cognitive deterioration is rare and seen only in advanced cases.12

Serum ceruloplasmin is a readily available screening tool but can be normal in 5–15% of patients.3 Urinary copper levels are typically more than 100 mcg/dL in patients with symptomatic Wilson’s disease. Free copper (non-ceruloplasmin- bound) will be elevated in serum. Liver biopsy is a sensitive and accurate test to diagnose Wilson’s disease.13 In patients presenting with either neurologic or psychiatric dysfunction, a combination of Kayser-Fleischer rings, elevated 24-hour urinary copper, and reduced ceruloplasmin essentially confirms the diagnosis of Wilson’s disease, thus precluding the need for liver biopsy.

Our patient’s initial presentation was encephalopathy with seizures. It was the absence of classic manifestations of Wilson’s disease early in the illness that led to a delay in diagnosis. Though rare reports of Wilson’s disease presenting initially as seizure exist, initial presentations as acute encephalitis are rare. In our case, the parents did notice the slow decline in school performance and deterioration in handwriting, but they failed to report these early.

This case demonstrates the importance of detailed history taking and clinical examination in any neurologic or neuropsychiatric presentation, despite advances in imaging and electrophysiology. Wilson’s disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis in young patients presenting with otherwise unexplained encephalopathy. Being a treatable disease, screening of Wilson’s disease should be conducted in any atypical neurologic presentation. In the future, as genetic testing becomes ubiquitous, the current challenges and uncertainties in diagnosing this condition are likely to be resolved.

Conclusion

Wilson’s disease is treatable albeit challenging to diagnose and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any unexplained neurologic or psychiatric dysfunction, particularly in young patients.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Informed written consent was taken from the patient and his kin.

references

- 1. Lutsenko S. Modifying factors and phenotypic diversity in Wilson’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014 May;1315(1):56-63.

- 2. Merle U, Schaefer M, Ferenci P, Stremmel W. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and long-term outcome of Wilson’s disease: a cohort study. Gut 2007 Jan;56(1):115-120.

- 3. Brewer GJ. Wilson’s disease: a clinician’s guide to recognition, diagnosis, and management. Boston, MA: Kluwer; 2001.

- 4. Machado A, Chien HF, Deguti MM, Cançado E, Azevedo RS, Scaff M, et al. Neurological manifestations in Wilson’s disease: report of 119 cases. Mov Disord 2006 Dec;21(12):2192-2196.

- 5. Ortiz JF, Cox ÁM, Tambo W, Eskander N, Wirth M, Valdez M, et al. Neurological manifestations of Wilson’s disease: pathophysiology and localization of each component. Cureus 2020;12(11):e11509.

- 6. Taly AB, Meenakshi-Sundaram S, Sinha S, Swamy HS, Arunodaya GR. Wilson disease: description of 282 patients evaluated over 3 decades. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007 Mar;86(2):112-121.

- 7. Prashanth LK, Sinha S, Taly AB, A Mahadevan, Vasudev MK, Shankar SK. Spectrum of epilepsy in Wilson’s disease with electroencephalographic, MR imaging and pathological correlates. J Neurol Sci 2010 Apr;291(1-2):44-51.

- 8. Kumar S. Wilson’s disease presenting as status epilepticus. Indian Pediatr 2005 May;42(5):492-493.

- 9. Pestana Knight EM, Gilman S, Selwa L. Status epilepticus in Wilson’s disease. Epileptic Disord 2009 Jun;11(2):138-143.

- 10. Sinha S, Taly AB, Ravishankar S, Prashanth LK, Venugopal KS, Arunodaya GR, et al. Wilson’s disease: cranial MRI observations and clinical correlation. Neuroradiology 2006 Sep;48(9):613-621.

- 11. Dening TR, Berrios GE, Walshe JM. Wilson’s disease and epilepsy. Brain 1988 Oct;111(Pt 5):1139-1155.

- 12. Frota NA, Barbosa ER, Porto CS, Lucato LT, Ono CR, Buchpiguel CA, et al. Cognitive impairment and magnetic resonance imaging correlations in Wilson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2013 Jun;127(6):391-398.

- 13. Pfeiffer RF. Wilson’s disease. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(4 Movement Disorders):1246-1261.