A 17-year-old male, with no comorbidities, presented with a mass from the left lateral chest extending to the back. At age seven, he had a small mass in the left lateral chest wall at the mid-axillary line which was excised in a periphery hospital (no official medical report). Six years after the surgery, another mass appeared just above the scar of the previously excised mass. The size of the mass increased dramatically over four years; therefore, the patient came to our center. On examination, the swelling was soft, lobulated, cystic, not attached to the overlying skin, extending from the left lateral chest to the back, measuring 13 × 7 cm anteriorly, 7 × 4 cm on the lateral chest, and 28 × 23 cm posteriorly [Figure 1]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large heterogenous mass measuring 17 × 6 × 20 cm, extending from the 4th to the 10th rib involving the left paravertebral muscles [Figure 2].

Figure 1: Showing a lobulated mass extending from lateral chest to the back measuring 13 × 7 cm anteriorly, 7 × 4 cm laterally, and 28 × 23 cm posteriorly.

Figure 1: Showing a lobulated mass extending from lateral chest to the back measuring 13 × 7 cm anteriorly, 7 × 4 cm laterally, and 28 × 23 cm posteriorly.

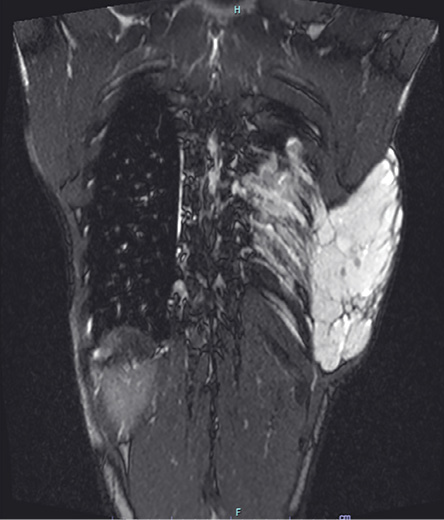

Figure 2: MRI showing a huge heterogenous mass (measuring 17 × 6 × 20 cm) extending from the 4th to 10th rib and involving the left paravertebral muscles.

Figure 2: MRI showing a huge heterogenous mass (measuring 17 × 6 × 20 cm) extending from the 4th to 10th rib and involving the left paravertebral muscles.

Questions

- What is the diagnosis?

- What are the MRI findings of this lesion?

- How will you treat this patient?

Answers

- Lymphovascular malformation.

- Fat-saturated T2-weighted coronal MRI of the chest wall showed a large, relatively well-defined solid soft tissue lesion in the left posterolateral chest wall extending to several intercostal and extrapleural spaces. The lesion showed marked T2 hyperintensity with few thin hypointense septa. Few rounded T2 hypointense foci were seen, which corresponds to calcification. No cystic spaces or fluid level and no fat within the lesion were observed. Post-contrast dynamic images reveal delayed heterogeneous enhancement of the lesion but no arterial enhancement, enlarged arterial feeders, or early draining veins. The presence of multiple calcific foci with central lucency within the mass is suggestive of phleboliths. Overall MRI features were of slow-flow vascular malformation with venous and lymphatic components.

- Sclerotherapy with bleomycin injections.

Discussion

Vascular anomalies affect up to 10% of newborns; they were classified in 1982 into congenital vascular malformations (CVMs) and vascular tumors. This classification has been revised by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies [Table 1].1,2 Whereas vascular tumors may regress with age, CVM never regresses on its own. They are subdivided into venous, lymphatic, arteriovenous, and combined malformations.3 Lympho-vascular malformations (LVMs), also known as hemangioma-lymphangiomas, are low-flow vascular malformations that consist of malformed lymphatic channels and account for about 12% of vascular anomalies.4 They can be classified into macrocystic (> 1 cm), microcystic (< 1 cm), or mixed cystic according to their cystic appearance. Moreover, they can be generalized or localized at the cutaneous, subcutaneous, fatty, or intramuscular levels.3 Our patient had a macrocystic type of LVM. Diagnostic modalities for LVM include ultrasound, MRI, and angiography. MRI is considered the best modality because of its soft tissue resolution. LVMs are usually well defined, lobulated, hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI, and hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted images.2,4 Macrocystic lesions are effectively treated by sclerotherapy, as in our case. Commonly used sclerosing agents are sodium tetradecyl sulfate, bleomycin (> 50% reduction in lesion size), and doxycycline. There is no consensus regarding the best sclerosing agent in treating macrocystic LVM. Our patient received three sessions of sclerotherapy; there was a gap of one month between each session. The size of the lesion decreased significantly after the third session; 8 × 8 cm anteriorly, 7 × 4 cm on the lateral chest, and 22 × 22 cm posteriorly [Figure 3]. Surgical intervention is reserved for patients that fail to respond to sclerotherapy. In contrast, microcystic LVMs are difficult to treat and are typically managed conservatively. However, symptomatic lesions are treated surgically. Surgery is considered the first line of treatment as sclerotherapy is ineffective in treating microcystic lesions, although recurrence happens in 40% of patients with incomplete excision and 17% with complete resection.2,5 Despite the advancements in managing vascular anomalies, CVMs remain a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to many physicians requiring a multidisciplinary approach.

Table 1: International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification for vascular anomalies approved at the 20th ISSVA Workshop, Melbourne, April 2014, last revision May 2018.

|

Benign

|

Capillary malformations (CMs)

|

CVM, CLM

|

Affecting arteries, veins, and lymphatics of large diameter.

|

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome

Parkes Weber syndrome

Servelle-Martorell syndrome

Sturge-Weber syndrome

Limb CM + congenital non-progressive limb overgrowth

Maffucci syndrome

Macrocephaly-CM

Microcephaly-CM

CLOVES syndrome

Proteus syndrome

Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome

CLAPO syndrome

|

|

Locally aggressive or border line

|

Lymphatic malformations

|

LVM, CLVM

|

|

|

|

Malignant

|

Venous malformations

|

CAVM*

|

|

|

|

Arteriovenous malformations

|

CLAVM*

|

|

|

Figure 3: Lymphovascular malformation after the third session of sclerotherapy.

Figure 3: Lymphovascular malformation after the third session of sclerotherapy.

°Defined as ≥ 2 vascular malformations found in one lesion; *High-flow lesions; CVM: capillary-venous malformation; CLM: capillary-lymphatic malformation; LVM: lymphatic-venous malformation; CLMV: capillary lymphatic venous malformation; CAVM: capillary arteriovenous malformation; CLAVM: capillary-lymphatic-arteriovenous malformation.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Verbal consent was obtained from the patient and his father to publish the images and the clinical findings.

references

- 1. Al Mahruqi G, Stephen E, Abdelhedy I, Al Mawaali H, Al Musalhi B, Al Balushi Z, et al. Congenital vascular malformations: a quick recap. Oman Med J 2022 Mar;37(2):e347.

- 2. Mulligan PR, Prajapati HJ, Martin LG, Patel TH. Vascular anomalies: classification, imaging characteristics and implications for interventional radiology treatment approaches. Br J Radiol 2014 Mar;87(1035):20130392.

- 3. Sadick M, Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular anomalies (Part I): classification and diagnostics of vascular anomalies. Rofo 2018 Sep;190(9):825-835.

- 4. Sharma M, Mallya V, Khurana N, Kumar P, Duggal R. Lymphovascular malformation - a report of two cases. J Clin Diagn Res 2017 May;11(5):ED03-ED04.

- 5. Sanlialp I, Karnak I, Tanyel FC, Senocak ME, Büyükpamukçu N. Sclerotherapy for lymphangioma in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2003 Jul;67(7):795-800.