| |

Abstract

The medical humanities, a cross-disciplinary field of practice and research that includes medicine, literature, art, history, philosophy, and sociology, is being increasingly incorporated into medical school curricula internationally. Medical humanities courses in Writing, Literature, Medical Ethics and History can teach physicians-in-training communication skills, doctor-patient relations, and medical ethics, as well as empathy and cross-cultural understanding. In addition to providing educational breadth and variety, the medical humanities can also play a practical role in teaching critical/analytical skills. These skills are utilized in differential diagnosis and problem-based learning, as well as in developing written and oral communications. Communication skills are a required medical competency for passing medical board exams in the U.S., Canada, the UK and elsewhere. The medical library is an integral part of medical humanities training efforts. This contribution provides a case study of the Distributed eLibrary at the Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar in Doha, and its collaboration with the Writing Program in the Premedical Program to teach and develop the medical humanities. Programs and initiatives of the DeLib library include: developing an information literacy course, course guides for specific courses, the 100 Classic Books Project, collection development of ‘doctors’ stories’ related to the practice of medicine (including medically-oriented movies and TV programs), and workshops to teach the analytical and critical thinking skills that form the basis of humanistic approaches to knowledge. This paper outlines a ‘best practices’ approach to developing the medical humanities in collaboration among the medical library, faculty and administrative stakeholders.

Keywords: Medical Humanities; Medical Libraries–Qatar; Medical Education-Humanities.

Introduction

Medical humanities courses in Writing, Literature, Medical Ethics and History can teach physicians-in-training communication skills, doctor-patient relations, and medical ethics, as well as empathy and cross-cultural understanding.1 The Premedical Program at the Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (WCMC-Q) in Doha, Qatar requires the completion of two one-semester First Year Writing Seminars (FWYS) taught by the Writing Program faculty. Students in the FYWS write six major essays on topics ranging from literature, history, philosophy, and sociology. This requirement is designed to teach future doctors the practical skills of how to write accurate and concise patient case histories, to communicate research findings and epidemiological information in bulletins and peer-reviewed journals to other colleagues or government agencies, and to provide health information and diagnoses both orally and in writing to patients and families. In addition, the writing seminars are also designed to teach students humanistic knowledge about the cultures, histories and socio-economic backgrounds of their future patients, since all of these factors play a role in the delivery of effective and culturally appropriate healthcare.

From a purely practical standpoint, there is a great deal of cognitive overlap in traditional humanities-based skills and medical diagnosis and treatment; for example, pattern recognition in visually examining and determining pathological from normal tissue, the same skill set that allows artists to create meaning from shapes and colors. As Bolton has pointed out: "do the sciences not also rely for their effectiveness on understanding, critical analysis, meaning, discernment, interpretation, visualization, and creativity, all fostered by subjects traditionally considered to be based on humanities and arts?"2

Rita Charon, M.D., has persuasively argued that stories are an inherent feature of much medical praxis (for example, medical ethics cases and the life narratives of health practitioners), and she proposes that ‘narrative medicine’ should form part of the medical curriculum.3,4 Shapiro similarly argues that self-reflection through writing about medical encounters and the physician’s role as healer and comforter, can help doctors "better understand and critically reflect on their professions with the intention of becoming more self-aware and humane practitioners."5 In addition, the medical humanities can aid in bridging the current wide gap between the biosciences and the unexplained, immeasurable and metaphysical elements of human existence (soul, spirit, the precise point of death, spontaneous remission of illness, etc.), so that doctors can attend to the whole patient, not just the disease.6 Medical stories also help doctors to "understand how patients feel about, and respond to illness, and how they interpret and relate to their carers."7

Students in their FYWS at WCMC-Q are expected to learn critical/analytical and research skills, and in addition are expected to learn how to use writing as a learning tool for discovery. Integral to this skill set is information literacy, which can be defined as the identification of information needs, and the retrieval and critical assessment of the information required to satisfy that need. In the early 1990s, David L. Ranum of the Interdisciplinary Knowledge Engineering Laboratory in Iowa argued that student success in medical informatics and information literacy courses in medical school could be greatly increased "if entering medical students had exposure to the basic ideas of information literacy prior to their exposure to the domain specific concepts from medicine."8 This viewpoint–that medical students need to be introduced to information finding strategies as early as possible in their educational careers–has been unanimously adopted both by the WCMC-Q medical librarians and the Writing Program faculty members who teach Medical Humanities in the Premedical Program.

Due to rapid advances in biomedical science, information skills are now a key competency for all healthcare practitioners. Thus the medical library, which stands at the heart of the information sciences in a medical college, is the obvious partner for providing materials, training and programs to support the teaching of medical humanities at both the premedical and medical levels. Aitken et al. reported success in embedding clinical librarians at the point of care to provide immediate literature searches for evidenced-based resources: notably "88% (of medical residents and clinical clerks) reported having changed a treatment plan based on skills taught by the clinical librarian."9 Medical librarian Megan Curran explains the many other ways that the medical library can support the humanities: from the simple (book clubs, essay contests, hosting medical humanities speakers, collection development in both leisure and medical humanities reading) to the more complex (information literacy courses, research training workshops, grant writing workshops, etc.).10 WCMC-Q has developed almost every area of library support for the medical humanities described by Curran. The specific Medical Humanities support programs introduced by the WCMC-Q DeLib library are described in detail below.

Discussion

The Distributed eLibrary (DeLib) Instructional Program focuses on undergraduate students as well as the teaching and research needs of the campus faculty. The program aims to develop independent critical thinkers with the ability to solve problems and question authorities. Lack of critical thinking skills is widely cited by Gulf educators as a key failing of the traditional kuttab-school education of the pre-oil era based on memorization. These traditional teaching methodologies still survive today in Gulf schools at all levels.11 In addition, the Instructional Program of DeLib stresses the ability to use the methods and materials characteristic of each knowledge area with an understanding of the interrelationship and the interconnectedness of the core areas. Continuing Medical Education (CME), a system to insure that doctors continually update their professional knowledge and skills, is now a legal requirement in many parts of the world for renewal of the medical license: the Instructional Program has responded to this need for Continuing Medical Education by designing instructional materials to not only help students develop a commitment to intellectual curiosity and life-long learning, but also to equip them with the practical skill set to fulfil their CME requirements. Furthermore, the Instructional Program encourages openness to new ideas along with the social skills necessary for both teamwork and leadership, as most medical care these days is carried out by teams. Another commonly discussed feature of Gulf educational systems is the reliance on the instructor for information, known as the banking model of education.12 The exercises and instruction developed by the Instructional Program, on the other hand, force the student to think independently and be self-directed: to make informed choices and take initiative.

In order to meet the information literacy needs of the WCMC-Q Premedical Program, the DeLib Library began developing a course entitled DeLib 101 to serve as the core of its information literacy efforts. The library also began collaborative pilot efforts in 2011 with both a humanities course (The First Year Writing Seminar) and science course (Biology). The First Year Writing Seminar (FYWS), supervised by the Knight Writing Institute on the Ithaca, New York campus of Cornell University, is one of two required writing courses taken by premedical students. Topics can include humanities themes such as literature, poetry and film, or medical humanities concentrations such the history of medicine, women in medicine, and Islamic medicine. Many of the goals of the Writing Seminar are identical to the efforts of the DeLib Instructional Program-critical and analytical thinking, information retrieval, basic humanities research skills, and weighing and assessing sources-and collaboration between the DeLib Library and the Writing Program instructors who use the medical humanities as course themes was therefore a natural development.

The goal of DeLib 101, which is still in development, is to provide a non-credit certificate of completion for premedical students to include in their admissions packet to medical school. The certificate demonstrates that the student has achieved a level of proficiency in the information skills that the librarian staff, guided by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Information Literacy Standards, has determined to be essential for success in the medical program.13

Specifically, the goals of the DeLib 101 course are to:

1. Deliver multiple online library tutorials teaching information literacy skills.

2. Provide in-class workshops mapped to ACRL Information Literacy Standards.

3. Offer workshops outside of classes, which support the information literacy skills for various levels: faculty, medical, pre-medical, research, staff, Foundation Program.

4. Create and implement a comprehensive assessment module:

a. Assess each information literacy session with 3-4 anonymously answered questions based on the session. Answer recording techniques can include: iClickers, paper print-outs, etc. Statistics are recorded.

b. Develop assessment based on reflection and recommendation that is not too time consuming to collect and interpret.

5. Promote and support subject expertise within the staff.

6. Provide support to librarians for continuous improvement of teaching skills and methods.

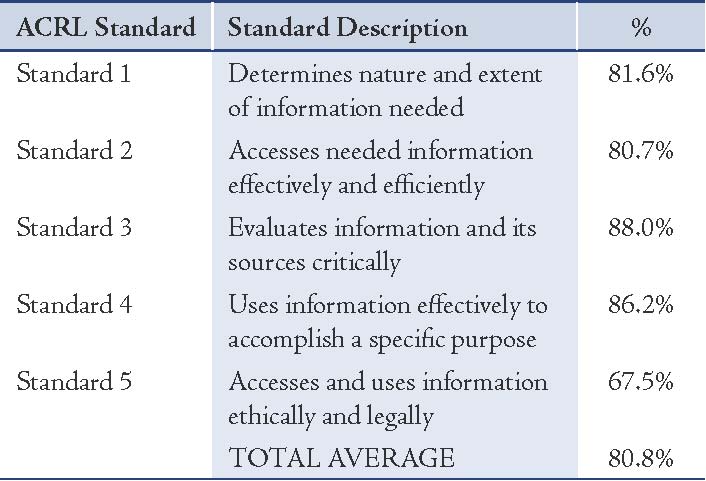

In order to assess if the current DeLib Instructional Program efforts were meeting the information literacy needs of premedical students, a pilot test with questions based on the ACRL Standards was administered to 40 premedical students in June 2011. The average score, based on the complete test, was 80.8%, well below our set pass rate of 90%. Scores for individual standards were as follows (see Table 1):

Table 1: Pilot test DeLib 101 scores (n=40) out of 100% possible total score, Biology and Writing Seminar students combined.

It was clear from these results that librarians had to focus on providing literacy skills in their classes and also in out-of class sessions. Between September 2010 and June 2011, 13 workshops were provided to premedical students. These workshops were at the request of faculty and normally intended to support curricular activities. Librarians added information literacy components but there was no real assessment to determine whether or not students were learning the skills being taught. At about the same time, librarians began a concerted effort to actively engage students in learning. This was accomplished by designing out-of-class sessions as well as in-class lessons that were activity based.

The pilot test was once again scrutinized, this time in order to determine problems within the questions themselves. If certain questions were uniformly answered incorrectly there could be any number of reasons; however, wording was changed to ensure the clarity of meaning and an effort was made to clear up the language of ‘Libraryese.’

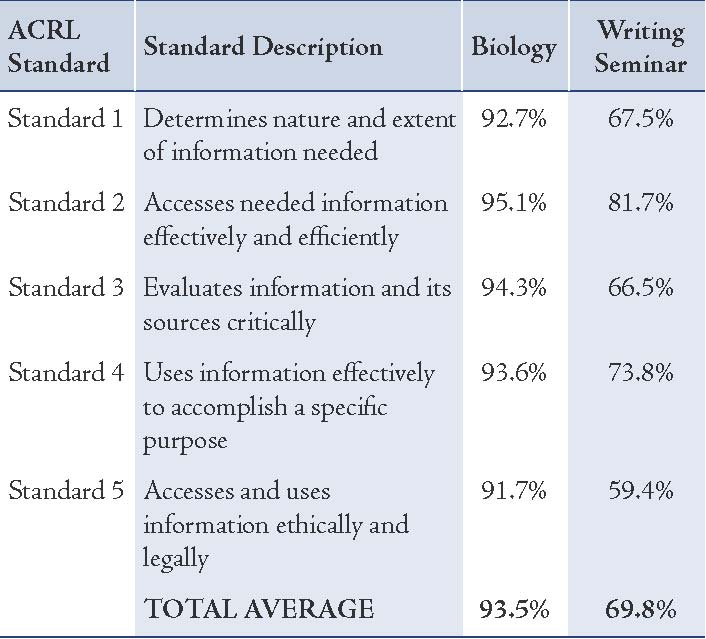

A meeting with the premedical Writing Seminar and Biology faculty to discuss the pilot test was arranged, a process that illustrates that a truly collaborative curriculum development that meets faculty needs, furthers the educational mission of the library, and serves students needs, must develop with feedback mechanisms and regular communication between stakeholders. These two courses serve 100% of pre-med students. The results from the pilot test were provided and discussed by faculty and the librarians. It was agreed at this meeting that two 50-minute sessions would be prepared by the liaison librarians for each course. Content of the sessions was directly targeted towards the information literacy standards. Based on the experience of the pilot quiz, the liaison librarians created a Mini Quiz for the Writing Seminar and Biology courses. Each quiz was made up of 20 multiple choice questions, again based on the 5 ACRL Standards, i.e., 4 questions per standard. The quizzes were also complemented by 4 short assignments: a) matching parts of a citation, b) legally and ethically paraphrasing a quotation, c) locating a print book and identifying parts, d) performing a database search, identifying keywords, refining a search, and locating and identifying 2 citations.

The quiz was weighted 60%, with 10% each for assignments. The mini quizzes and assignments were made available to students on the Angel Learning Management system. Some professors made the quiz and assignments mandatory and others made it optional; not surprisingly, when the quiz was optional there were no submissions.

In one Writing Seminar class, taking the quiz and scoring above 90% represented 10% of their total grade. All students in the class took it, revealing the importance of appropriate incentives for time-pressed premedical students who naturally prioritize grade-bearing academic activities over optional ones. In another Writing Seminar, class librarians used allocated class time for a library session to allow students to take the quiz, which they all did. The Biology professor gave students the option to take the quiz or complete some homework. The students could choose the highest grade (quiz or homework) to count towards their final grade. Out of 42 total students, 29 completed the quiz and assignments.

How well did they do?

The average score for the Writing Seminar Mini Quiz and assignments was 69% and the Biology average score was 93.5% (Table 2). Although there is a significant difference between the two scores, this difference can be attributed to the time of year the quiz was taken and the amount of library instruction given to the students prior to the quiz. For example, the Writing Seminar classes took the quiz and assignments fairly early in the academic year, in September or October. These students had only had one or two classes prior to taking the Mini Quiz. Biology students, however, took the Mini Quiz at the end of the semester, in late April of 2012. Many of the students who took the test had also taken the Writing Seminar quiz in early September. Since the Biology class and Writing Seminar class represent the same cohort, this time-series quasi-experimental set up provides evidence that the Instructional Program information literacy workshops offered over the course of the semester increased student performance and learning on the Mini Quiz. Based on this pilot data, a more controlled and randomized method in a future study could reveal more conclusively that the information literacy interventions (training sessions and tutorials) improved information literacy learning outcomes among premedical students. A similar result was recorded in a 2011 study of 8,701 undergraduates at Hong Kong Baptist University: a strong positive correlation was established between the number of information literacy sessions attended and higher GPA.14

Table 2: DeLib 101 Mini Quiz scores out of 100% possible total score, stratified by course (Biology / Writing Seminar).

Follow Up Development

To measure and improve learning outcomes, student learning in library sessions must be assessed. A new Assessment Coordinator was tasked with determining the learning of students. Short questionnaires that directly relate to the topic of the session are now being administered at the end of each session and scored. Hopefully, this new assessment method will provide information to assist in the design of the library classes. The DeLib is also in the process of creating online tutorials with a newly hired Instruction Design Librarian. These tutorials will complement what is being taught in the classroom and also the out-of-class sessions. Our students are very focused on mobile devices and we are a distributed eLibrary ("e" stands for "electronic") with a primarily electronic collection of online journals, databases and ebooks, so the information should be available whenever or wherever a person is ready to use the information.

We would also like to encourage faculty to include mini-quiz grades in a student's final grade. This seems to be the best enticement to get students to complete the quiz. Major support from faculty and good advertising will be needed to encourage students to take the final DeLib 101 exam which is required for the awarding of the information literacy certificate. Librarians have visited the premed classes to discuss the DeLib 101 exam and will again advertise it closer to the time when medical school applications are due, usually in December.

Supporting Other Initiatives in Medical Humanities

Besides DeLib 101, the Instructional Program of the DeLib has been active in supporting other areas of both humanities and medical humanities. A WCMC-Q humanities faculty member in conjunction with the librarians developed the 100 Classic Books reading collection spanning Homer to Naguib Mahfouz. Through a link to the collection on the DeLib home page, anyone can write an online review of any of the books and recommend other books with the goal of expanding the collection to 200 volumes. Another faculty member initiated the "Book Pitch" in which faculty, staff and students are encouraged to write a book review and publish it on the library website.

The DeLib library also engages in extensive collection development of both humanities and medical humanities materials, including medical sociology, medical history, medical ethics, and medical philosophy. Medical dramas on DVD–for example, the TV programs House, Grey’s Anatomy, and ER– are frequently used by faculty members to teach medical ethics, the sociology of medicine and medical history. Also, a medical school faculty member donated to the library her personal Classics of Medicine book collection consisting of reprints of historical medical texts ranging from the Egyptian medical papyri to 19th century textbooks. Books on doctoring and narrative medicine are also requested by faculty and used in their courses.

A WCMC-Q professor of Neurology recently developed with the DeLib his "Neurosciences at the Movies" collection of movies, video clips, and TV programs all with a neurological component. With the current WCMC-Q medical curriculum undergoing serious revision after the publication of the "Flexner II" report in 2010, a comprehensive appraisal of U.S. medical schools by the Carnegie Foundation,15 the neurology faculty member felt a need for new ways of teaching and reaching students to improve motivation and retention, and to embrace different styles of learning such as visual and indirect instruction. Some planned educational activities which will draw on "Neurosciences at the Movies" include utilizing film in the classroom to enhance lessons, asking students to write short paragraphs on a viewed scene (critical engagement), and using clips to initiate discussions and analysis of the social (i.e., non-medical) aspects of brain and mind.

The Distributed eLibrary Instructional Program is also committed to supporting the faculty and educational mission at WCMC-Q by providing easy access to resources for all courses. Course Support Guides created by the liaison librarians in collaboration with the faculty provide access to library resources for students for each of their classes. In the past, they consisted of subject guides and other library resources. The subject guides consist of books, databases, ejournals, and websites specific to a particular subject, all accessible through a single page or portal. The subject guides are mostly created by the librarians, although sometimes faculty input is requested depending on the subject. The subject guides are embedded within the course support pages. Examples of subject guides include: Writing Seminar, Biology, Pediatrics, Genetics, and Alternative Medicine.

The library now creates course support pages and subject guides using the software Libguides. Libguides offer a more intuitive and interactive way of providing access to resources for students. It does not require the use of programming. It offers a very simple copy/paste/attach interface that anyone who uses computers can use. It also offers an option for using html code to create a Libguide page for those who are more adept at programming. Once the pages are created, Libguides provides statistics on how many times the pages are used. Each of the Writing Seminar sections has its own Course Support page, as each section covers a different aspect of literature and humanities. In addition to accessing library resources, course support pages provide links to outside resources including videos, audio recordings, images, and other resources. These pages foster inspiration and creative thinking for students as they complete assignments for their Writing Seminar classes. For example, students can browse the material for research paper topics.

Collaboration between the librarians and the Writing Seminar professors is key to creating Course Support Pages and Subject Guide pages that help students with their coursework. The process is as follows: as any professor does, all the Writing Seminar professors lay out their syllabus and class schedule during the spring and summer before classes begin in the fall semester. The librarians then meet with the Writing Seminar professors to coordinate teaching workshops for the students according to the syllabus. These workshops are taught before student assignments are due so that students will use library resources for their assignments. The librarians teach workshops on research basics, database searching, and plagiarism. For example, for one professor’s Writing Seminar class, one of the many assignments that students must complete is to write a research-based paper on Islamic medicine in which they must find peer-reviewed sources using library databases. The librarians collaborate with the professor to determine which databases the students should use to find the most relevant information on their topics. For this topic, the librarians taught the students how to use Academic Search Premier and Proquest. Before the librarians began the training on these databases, they showed the students how to take a research question and break it up into possible keywords and synonyms that would yield relevant search results in the databases. This is a prime example of the kind of information skills that students will need to retain throughout their careers, as medical knowledge is shifting rapidly and the volume of knowledge is also growing exponentially; thus they will need to search and locate relevant new knowledge in their medical speciality, and also need to assess their sources for medical accuracy and validity.

During the workshops, the librarians show the students how to access the Writing Seminar Course Support page for their professor. They are then shown the different resources on this page that will help with their assignments. The class syllabus is posted on the first page for easy student reference, as well as the assignment sheets and grading rubrics. Other sections of the Libguides page offer resources on Islamic medical scholars, such as Ibn Zuhr, Ibn Sina and Al Rhazi who are studied in the course. Another tab contains a video on how to write an essay and also a link to the OWL Purdue Online Writing Lab. PowerPoint presentations used to demonstrate the research basics are also posted on the Course Support page.

In addition to this Course Support page, a Subject Guide page on Islamic medicine is available to the students. Various books, databases, journals, and websites relevant to Islamic Medicine are found in this subject guide. Some of these resources include the Index Islamicus database, the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, an ebook entitled Legacy of Arab Medicine during the Golden Age of Islam, and a link to the website of the International Institute of Islamic Medicine. Students will also find a link to the library’s Course Reserves on Islamic Medicine. Course reserves are books that the library has set aside for use with a specific class. Some of these books are written in Arabic. This page is relevant not only to the professor’s Writing Seminar class, but also to the medical school as a whole, given the demographics the medical school serves and its location in the Middle East.

One of the key critical skills that the librarians teach in their workshops is Research Basics. Librarians teach students the steps necessary to find relevant articles once they have formulated a research question (hypothesis). These steps include formulating the research question, deriving keywords from the research question, deriving synonyms and truncation from the keywords, linking the keywords/synonyms/truncation together with Boolean operators, choosing which database to use, and finding relevant articles. All of these steps are fundamental for the student in conducting research. It is of particular importance at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar due to the medical curriculum. The medical school follows a Problem Based Learning (PBL) curriculum. A PBL curriculum in a medical school entails having a clinical case scenario where the student is given a patient who presents with a medical condition. Professor Ashraf Husain of King Saud University Medical College in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, believes that a hybrid PBL model (which combines PBL with traditional medical education such as lectures) is the most suitable methodology for Middle East medical schools.16 The students must then make a diagnosis for a patient based on the clinical case scenario and lab tests conducted. One course in particular, Evidence Based Medicine in Medical Year 1, develops students’ clinical query skills in that it helps them develop a clinical query from the case. The librarians are all co-facilitators for this course and play a significant role in helping students with developing clinical queries, in addition to helping with other skills.

The clinical query skill development in medical school is an extension of the research basic skills workshops taught to the pre-medical students. This reinforcement is intended to promote long term memory retention and more thorough mastery of these skills. In both cases, the student must develop a research hypothesis (humanities) or clinical question (evidence based medicine), develop keywords, derive synonyms and truncation from the keywords, link these keywords together with Boolean operators, choose a database, and find relevant articles. The skills are different in medical school and for the EBM course in particular, in that the articles chosen are critically analyzed and used to guide patient care and answer the clinical query. Therefore, the librarians start to develop these basic research skills in students early in Pre-med Year 1, with the hopes that these skills will become routine for students when they enter medical school.

Conclusion

The teaching of medical humanities and the collaborative processes between faculty and the WCMC-Q DeLib librarians are well developed, and both the DeLib Library and the Writing Faculty who teach medical humanities expect to innovate further in this area in the future. Due to Qatar’s commitment to diversifying its economy away from hydrocarbon production towards knowledge economy activities, education and research are currently extremely well funded in Education City, the branch campus consortium where WCMC-Q resides. The DeLib Library plans to expand its quiz question bank for information literacy testing and develop new assignments. The ultimate goal is to make DeLib 101 a required 1 credit-bearing course in the Premedical Program. Librarians are also exploring the creation of new online tutorials to teach specific information literacy concepts so that face-to-face in-class library sessions are maximized and do not take too much time away from the regular activities of the faculty member’s class. With the explosion of online databases and publically accessible scholarly search engines (such as Google Scholar), information literacy skills, particularly the assessment of appropriate sources given the enormous amount of ‘junk’ information on the Internet, are now critical in all professional disciplines. The best practices for information literacy in a medical school developed by WCMC-Q librarians and premedical faculty could have wider application to other fields since they are grounded in the carefully thought out ACRL standards which can be universally adopted in any academic endeavor.

Acknowledgements

The authors report no financial or personal conflicts of interest related to this research.

References

1. Weber AS. Teaching disciplinary historical foundations augments meta-cognition in health sciences education. Edulearn 10 Proc 2010; 1257-1263.

2. Bolton G. Medicine, the arts, and the humanities. Lancet 2003 Jul;362(9378):93-94.

3. Charon R, Montello M, eds. Stories Matter: the Role of Narrative in Medical Ethics, New York, NY, Routledge, 2002.

4. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness, NY, Oxford UP, 2008.

5. Shapiro J, Coulehan J, Wear D, Montello M. Medical humanities and their discontents: definitions, critiques, and implications. Acad Med 2009 Feb;84(2):192-198.

6. Brawer JR. The value of a philosophical perspective in teaching the basic medical sciences. Med Teach 2006 Aug;28(5):472-474.

7. Hooker C. The medical humanities - a brief introduction. Aust Fam Physician 2008 May;37(5):369-370.

8. Ranum DL. "Pre-medical" informatics. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care 1993;743-746.

9. Aitken EM, Powelson SE, Reaume RD, Ghali WA. Involving clinical librarians at the point of care: results of a controlled intervention. Acad Med 2011 Dec;86(12):1508-1512.

10. Curran M. A call for increased librarian support for the medical humanities. J Med Libr Assoc 2012 Jul;100(3):153-155.

11. Weber AS. Comparative analysis of national higher education policies in the gulf cooperation council (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, UAE, Kuwait). Proc HICE 2012:3153-3174; Al-Misnad S. The Development of Modern Education in the Gulf, London, Ithaca Press, 1985; Weber AS. American education in the Arabian Gulf. Proc Eur Soc Sys Inn of Ed 2012.

12. Weber AS. Learning through writing for gulf medical students. In P. Davidson (Ed.), TESOL Arabia Conference 2011, Dubai, TESOL Arabia.

13. Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). "Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education." Web. <http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency>.

14. Cmor C, Wong SH. Measuring association between library instruction and graduation GPA, Coll Res Lib 2011:65-81.

15. Cooke M, Irby D, O' Brien B. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2010.

16. Husain A. Problem-based learning: A current model of education. Oman Med J 2011 Jul;26(4):295.

|

|